A Peek Into the Collection: Faith Ringgold

For our second look into the Neuberger Museum’s permanent collection, we’ve chosen to highlight a work by Faith Ringgold, an activist artist best known for her narrative painted quilts from the 1980s. Our piece, however, is the first in her earlier American People series of 20 oil paintings.

Ringgold started the series in 1963, against the backdrop of the Emancipation Proclamation’s 100th anniversary, the civil rights leader Medgar Evers’ assassination, and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s “I Have A Dream” speech. The painting, Between Friends, also reflects Ringgold’s personal experience with racism in the summer of 1963, during which she faced tense interactions with white women at her host’s poker parties in Martha Vineyard.

Analyzing the Work

Rem Ribeiro

While the artist Faith Ringgold is best known for her oeuvre’s theme of the black experience in America, it is paramount to understand the presence of the black female American in this complex and ever-changing dynamic. Looking towards the work American People Series #1: Between Friends (1963) now—in the fourth wave of feminism—can be extremely fruitful and rewarding. Ringgold’s unique and specific means of navigating the picture plane through color and shape further show the tension between both gender and race. In Between Friends, Ringgold speaks directly to the personal nostalgia of navigating assimilation and acceptance into predominantly Caucasian spaces.

Through a psychoanalytic formal analysis, Ringgold excels in creating polarity between the woman on the left and the woman on the right. The black woman presented on the left is composed with a warm color palette, as well as having rounder, softer shapes in her face, arms, and breasts. The white woman on the right, however, is painted with cool colors, a flatter chest, and angular facial features. While the woman on the left has rosy cheeks, clear, rounded eyes, and the subtle smile of red lips, the woman on the right has sallow cheeks, tight lips, and dark, void-like eye sockets. The tension between the two, both physically and emotionally, is at its utmost potential. The tight cropping of the picture plane, accompanied by the bright red scaffolding of two doorways, forces the two women to be in the closest of encounters. Here, there is no means of escape; they must both confront the situation at hand: the problematic disability of female empathy, further prevented by race relations.

Since the third wave of feminism, intersectionality and internationalism have pushed towards the forefront of the feminist movement. Now more than ever, due to very recent and still pressing racial tensions in America, and on a global scale, feminism can help us find a genuine space of community and consolation. Rather than allowing this “red scaffolding” to further prevent us from achieving any semblance of understanding and equity, we should look towards the works of Ringgold, and many other womxn of color in the art world, to always continue this discourse and create dialogue around other important questions encompassing identity and infrastructure.

It is up to us to heed Ringgold’s warning: “Every time people struggle, they survive, they do better, and then they forget, and they end up back where they started from.”

Faith Ringgold with self-portrait in American People, Black Light: Faith Ringgold's Paintings of the 1960s at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC (June 19, 2013). The exhibition was organized by and debuted at the Neuberger Museum of Art in 2010.

American People, Black Light at the Neuberger Museum

Gabrielle Bohrman

The Neuberger Museum purchased Between Friends for its permanent collection in 2011, following a retrospective exhibition of Ringgold’s paintings from the 1960s. In addition to her American People series, the exhibition also included her late 60’s Black Light paintings which conveyed themes from the “Black is Beautiful” movement. American People, Black Light, was toted by several publications as the first comprehensive exhibit of Ringgold’s 1960s paintings. These paintings were not as commercially successful as her later quilt paintings, perhaps given her identity as a Black woman trying to break into the white Caucasian dominated art scene at the time.

Furthermore, the series boldly depicted middle-class black and white people in situations together, calling attention to America’s race problem. Unlike some of her predecessors, including Alma Thomas who avoided overly politicized content in order to fit within museum’s aesthetic mold, Ringgold confronted the issue of race head-on with clear and graphic works.

“…I was not concerned with friends or enemies. Being unknown and a newcomer, I had neither. I was concerned with making truthful statements in my art and having it seen. Younger black artists objected to my paintings of white people. Some neither understood nor accepted my need to make images of anyone but black people.”

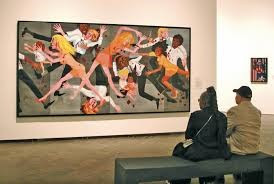

The rest of the American People series include a variety of confrontations between white and black people, demonstrating the inequal power dynamics in everything from business, and school, to the arts. The final painting in the series, Die, is a chilling mural reimagining the riots that took place in urban cities such as Detroit in 1967. Ringgold emphasizes that no one is spared from the violence, as the 12-foot piece portrays all races, ages, and genders, fighting or fleeing the bloody battle on the streets. A pair of interracial children clutch each other in the center of the chaos, a detail that stood out to me when I viewed the piece at the MoMa last year. I understood this as Ringgold’s warning to the next generation, who are born without prejudice and hatred, but are capable of learning it from society.

Faith Ringgold and her late husband, Burdette (Berdie) Ringgold, at the Neuberger Museum of Art, 2010, viewing the artist's painting, The American People Series #20: Die (1967)

Coinciding with Ringgold’s 80th birthday in 2010, the Neuberger Museum’s American People, Black Light exhibition uncovered paintings that had previously been omitted from display and discussion in the art community for over 40 years. Recovered by exhibition co-curators, former Neuberger director Thom Collins and current Neuberger director Tracy Fitzpatrick, in collaboration with ACA Galleries, the works included in the show were conserved and framed and readied for exhibition. The museum’s founding patron, Roy R. Neuberger had previously developed a relationship with ACA Galleries and purchased some of his first pieces from there in 1937. Faith’s daughter, Michele Wallace, wrote the main for the catalogue. The exhibition went on tour to the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, the Miami Art Museum (now the Pérez Art Museum Miami), and the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

Given a museum’s power to reflect and shape our perception of societal issues, we have a responsibility to discuss our history from a diversity of perspectives. In this pivotal year following mass protests against racial injustice, it is crucial that we discuss and amplify black artistic voices. Faith Ringgold has advocated for racial and gender inclusivity for over 60 years, from leading protests against major institutions including the Whitney Museum of American Art, to risking arrest by taking part in “The People’s Flag Show” exhibition. With Between Friends on display at the Neuberger Museum this spring, Rem and I thought it was important to share Ringgold’s vast impact on the contemporary art world with the Purchase College community.

Gabrielle Bohrman

Neuberger Museum of Art

Fall 2020 Communications Intern

NEU Student Voices Blogger

Rebecca Elisabeta Marya (Rem) Ribeiro

Neuberger Museum of Art

Neuberger Archival Research Fellow, 2020-2021

MA Modern and Contemporary Art, Criticism

and Theory, M+ Curatorial Studies track