Desara Leka ’25 and Arianna Strickland ’28

Literary Analyses of Mario Alberto Zambrano’s Lóteria by Desara Leka ’24 and Airianna Strickland ’28

Zambrano’s Lotería: Free of the Past

By Desara Leka

In Mario Alberto Zambrano’s novel Lotería, the themes of family dynamics, boundary-breaking, abandonment, courage, and cultural identity saturate the narrative, creating a rich tapestry for the protagonist’s journey. Luz Castillo faces the challenges of a lifetime dependent on parents who are not only abusive but emotionally immature. Traumatic events mark this journey, and reveal her remarkable courage to move forward. At an age when children typically experience the most freedom, Luz finds herself yearning for liberation from a constrained reality. In the chapters “La Sirena,” “El Camaron,” and “La Estrella,” Zambrano presents the side of Luz that is protecting, caring, and forgiving. The game of chance takes on new meaning as eleven-year-old Luz navigates the complexities of her cultural heritage, self-identity, and family drama through the cards. Through her eyes, we witness the duality between confronting and forgiving the past.

In “La Sirena,” Luz’s longing for freedom and maturity is portrayed through the admiration of the mermaid, which symbolizes hope amidst her reality. Luz is captivated by the mermaid not because of her beauty, as one might expect from an eleven-year-old, but because this creature is free. “Not because she was pretty or grown-up but because wherever she lived nothing and no one could touch her and she could swim wherever she wanted” (Zambrano 77).

This admiration reflects Luz’s desire to escape. She gives us a remarkable insight into freedom and the necessity to move forward. The mermaid represents an ideal life where no one could touch her, conveying that not only does Luz long for freedom to live wherever she would like, but also freedom from the abuse and the violence in her family. The mermaid can be seen as Luz’s hidden self—strong, courageous, and free-spirited. In this chapter she describes, “I’d wiggle from one side of the pool to the other, humming a song with my eyes wide open, not knowing whether I was crying or not because I was underwater” (78), capturing her internal battle with the weight of her emotions and her parents’ negligence. The water itself poses freedom and danger, as it tells us that Luz’s liberation comes with sacrifices. As she goes deeper into the pool and hums the song, she reveals that she is trying to find her voice and assert her identity, finding clarity within herself. This water is her sanctuary and battleground, where she wrestles with her past, fears, and desires. Zambrano portrays the struggles and the beauty of the human spirit who always finds the way to the shore.

In the chapter “El Camarón,” the duality between attachment and abuse creates a haunting depiction of bonds. Luz’s observation of her father’s actions—his self-punishment following his violent outburst—displays a complicated emotional wreck where love and pain coexist. The moment he hits Estrella hard enough to cause her to go unconscious represents a devastating cycle of violence that is justified by the father’s warped sense of morality. Luz articulates this conflict when she says, “You’d think I hate him. But it doesn’t matter; it doesn’t mean I don’t love him”(158). This statement encapsulates her struggle to separate her affection for her father from the thought that you can still love someone you hate. Raised in an abusive environment, the “love” within this household is expressed through violence, which is all Luz has known throughout her life. Luz recognizes that her father’s violent tendencies stem from the belief in right and wrong: “That night I figured he fought us not because he didn’t love us but because he believed in right and wrong”(159). This acknowledgment indicates that he considers his actions as enforcing discipline, revealing how love can manifest as control and punishment. The dynamics of the family and the perception of love, especially from Luz, the youngest, is not defined by hugs or kisses or gentleness and comfort, but rather by a blend of control and abuse, which leads her to convince and assure herself that this is how love is shown. This chapter not only touched on the normalization and the excuses of the abuse but also the cycle that cannot be stopped easily; in familial situations where there is love and loyalty the lines of morality and abuse are blurry, and Luz is a child who is trapped because she adores her father and is loyal to him. The symbolism of the “El Camarón” card juxtaposes the frozen shrimp in the freezer. As Luz pulls out the frozen bag of shrimp to help her father, who harmed himself because he hit his daughter, reveals Luz’s real devotion and true feelings. The shrimp represent a frozen state of emotional trauma, indicating how she is innocent and trapped in the façade of normalcy. Luz’s complex feelings toward her father highlight the tragic reality that love can be entangled with abuse. Nonetheless, in this chapter Zambrano reveals the part of Luz that is nurturing, caring, and compassionate, unlike her father, illustrating that she is able to break this cycle by sharing the love that she deserves to be given.

While navigating through the life she was born into, in the chapter “La Estrella” it’s revealed that this quest for freedom becomes twisted by the chaos of Luz’s surroundings and the need to be the one who protects this family. Luz describes the traumatic scene when the police arrive to arrest her father for the suspected murder of her mother. The tension escalates as Luz witnesses her father, already intoxicated, struggle against the officers trying to handcuff him. She knows her father is innocent. In her eyes, her father is on a pedestal and she looks up to him.

Luz’s assumption that her sister Estrella has betrayed them intensifies her emotional turmoil. As she rushes to her father’s room and grabs the rifle from under the bed, the gravity of the moment becomes palpable. As an immigrant family, her fear heightens, and the potential danger posed by her father’s arrest complicates her feelings of loyalty and protection toward him. Luz’s thoughts and actions reflect her deep-seated loyalty to her father, evident in his look: “Papi looked at me, and I knew by the way he looked at me he wanted me to do whatever I had to do”(229).

This moment reveals her internal battle, caught between devotion to her father and the horrific circumstances unfolding before her. Luz’s desire to emulate her father reflects her need for validation and connection, making her view herself almost as an extension of his identity or him as an extension of her, “He saw me and wanted a weapon of his own”(230). Not only does Luz feel the need to be like her father; a provider, a strong and authoritative figure, she also the need to become the person who saves this family, as if deep inside herself she is the one who needs to be saved.

In Zambrano’s Loteria each of the cards is one of Luz’s memories. Reliving her past, she confronts joyful but heartbreaking aspects of her life. Through her unique perspective, Luz processes trauma and abuse with purity. In every chapter, there is always a positive event, casting her as a person who sees the light in the dark. Her deep love for her family compels her to make significant sacrifices that lead to many painful outcomes and reveal the complexities of familial loyalty amid abuse. Still, Luz’s innocence is yet to be taken. Luz’s journey not only illustrates the difficulties of navigating trauma, it also emphasizes the strength to forge a path. The ongoing course of freedom is underscored by Zambrano in this novel, in a beautiful tapestry that resonates with anyone who has endured pain and longs to forgive and be forgiven. Luz’s story serves as a reminder for every reader of Loteria that healing is possible and starts from within; it can touch the darkest and most haunting memories, yet is ultimately necessary.

Work Cited

Zambrano, Mario Alberto. Lotería: A Novel. Harper Collins, 2014. Accessed 2 December 2024.

Whispers of Strength: Finding Light in the Shadows of Trauma

By Airianna Strickland

Trauma, whether one-time, multiple, or long-term recurring occurrences, affects people differently. Some may clearly exhibit criteria for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while many others will have resilient reactions or brief subclinical symptoms or repercussions that do not meet diagnostic criteria. The effects of trauma might be subtle, insidious, or completely catastrophic. The impact of an incident on an individual is determined by a variety of elements, including the individual’s traits, the nature and characteristics of the event(s), developmental processes, the significance of the trauma, and sociocultural factors (“Understanding the Impact of Trauma - Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services - NCBI Bookshelf”).

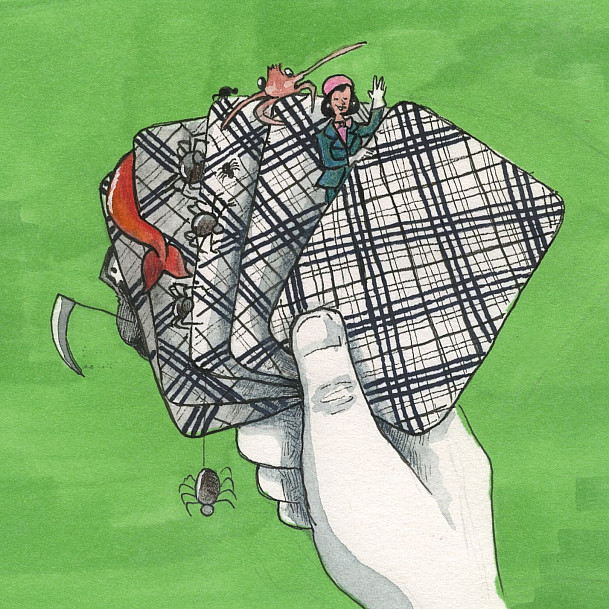

Mario Alberto Zambrano novel Lotería is narrated by Luz Castillo, a young girl grappling with her family’s unraveling. Zambrano explores how chance, cultural traditions, and trauma converge to shape Luz’s sense of self. Through her interactions with the Lotería cards, Luz confronts fragments of her memory, much like the unpredictable drawing of cards from the deck. This randomness reflects the chaos of her life, disrupting any clear path toward healing. The cards La Araña (The Spider), La Dama (The Lady), and La Muerte (Death), depict how Zambrano uses these symbols to delve into the key themes of personal agency, cultural expectations, and the complexity of familial bonds, which offers a layered portrayal of Luz’s fractured identity.

In the chapter titled “La Araña,” the spider becomes a multifaceted symbol for Luz’s entanglement in both emotional pain and questions of faith. Throughout the novel, Luz’s trauma is not something that can be easily understood or resolved—it is something she is stuck in, much like a web. Julia is a character (the counselor) who embodies deep emotional pain, using her own struggles to connect with Luz. When Julia tells Luz, “…the reason I don’t say anything is because I’m in deep pain. Like if pain were something she knew looked like me” (Zambrano 7), the spider becomes a metaphor for how Luz’s trauma defines her in the eyes of others. The comparison between Luz and a spider trapped in its own web reflects her inner turmoil: her pain is inescapable, and she feels suffocated by it, just as a spider is confined within the confines of its own web. This image of being consumed by pain without the ability to communicate it speaks to the silent, isolating nature of trauma that permeates the novel.

In addition to embodying her trauma, the spider represents Luz’s conflicted relationship with faith and fate. Throughout her reflections, Luz vacillates between acceptance of God’s will and a desire for control over her circumstances. She remembers the prayers she once whispered in the dark, telling God that she loved him and wanted to follow his will. However, her lingering doubt and frustration become evident when she questions whether her mother should have named her “Milagro” (miracle) instead of Luz (light), as if a different name might have spared her from her current suffering: “Maybe if she named me Milagro instead of Luz this would’ve never happened” (7). This suggests that Luz views her suffering as a cosmic error, something that could have been avoided had fate, or God, dealt her a different hand. Contemplating her name causes her identity to slip away each time she questions what about her, is “her.”

The presence of spiders crawling through Luz’s room serves as an extension of her thoughts on divine surveillance and omniscience: “It’s not like you don’t see them… when we crawl in our heads the way these spiders crawl over furniture” (1). Here, the spiders take on a dual role. On the one hand, they represent God’s omnipresent gaze, constantly watching over Luz and her family’s suffering. On the other hand, they mirror Luz’s internal state, as she grapples with her inner thoughts and memories—constantly creeping, never resting, and always lurking in the background. This tension between God’s perceived inaction and Luz’s emotional stagnation reflects the novel’s broader theme of the randomness and cruelty of fate, suggesting that trauma is something neither divine intervention nor personal will can easily resolve.

In the chapter titled “La Dama,” Zambrano delves into the societal and cultural expectations of womanhood, particularly through the lens of Latina femininity. In Mexican culture, La Dama often symbolizes grace, poise, and the traditional role of women as nurturers and moral guides within the family. However, Luz’s interactions with this card reflect her resistance to these expectations, especially in light of the trauma that has fractured her sense of identity. Early in the chapter, she admits, “I understood but I never felt like listening” (42), a confession that captures the conflict between knowing what is expected of her and feeling unable—or unwilling—to fulfill those roles. This struggle not only emphasizes the weight of societal standards Luz carries, but also emphasizes her journey toward self-definition as she navigates the tension between cultural identification and personal agency; an example of this is when Luz defies the people trying to help and care for her, like Julia and Tencha. Finally, her resistance to these traditional duties serves as a striking commentary on the constraints imposed by society’s expectations on women, particularly in Luz’s cultural context.

Luz’s reflections on her aunt Tencha’s advice offers a window into the tension between cultural and religious expectations. Tencha tells her, “You see us better than we see ourselves. Sometimes you find a way inside us to show us who we really are. But you have to let him in, she says. You have to open your heart” (44). This advice emphasizes the importance of faith and introspection as tools for personal growth and self-understanding. However, Luz’s reluctance to “let Him in” suggests a deeper disillusionment with the role faith is supposed to play in guiding her life. Luz’s relationship to faith and belief in God is complex. Throughout her narrative, her battles with trauma and search for meaning point to a turbulent relationship with spirituality. While she struggles with feelings of abandonment and uncertainties about faith, moments of hope and longing suggest that she may still seek a connection to a higher force, despite her doubts. This conflict echoes the novel’s overarching themes, in which faith gets interwoven with personal and familial struggles. Her resistance to opening her heart, in this case, is both literal and symbolic—she feels disconnected from the expectations imposed on her by her family, her culture, and her faith. This reluctance also reflects Luz’s struggle with cultural expectations of womanhood, especially in the context of her family’s trauma. “La Dama” represents an ideal of femininity that is unattainable for Luz, who has been shaped by chaos and loss. In the absence of a nurturing maternal figure and the breakdown of her family’s traditional roles, Luz’s relationship to femininity becomes fraught. She cannot reconcile the idealized image of La Dama with her own lived experience, creating a tension that further fractures her sense of identity. This chapter, like the card itself, explores the complexities of cultural identity, particularly how trauma disrupts traditional expectations and leaves individuals feeling alienated from their own cultural narratives.

In the chapter “La Muerte,” Zambrano shifts the focus to grief and the idealization of the past, as Luz reflects on her mother’s absence. This chapter is pivotal in exploring how Luz uses memory—and particularly idealized memory—as a means of coping with her family’s trauma. The card La Muerte, often associated with literal death, in this case represents the emotional and relational deaths that have occurred within Luz’s family. The loss of her mother as a stable, nurturing figure haunts Luz throughout the novel, and she frequently retreats into memories that idealize her mother, even when these memories conflict with reality.

Luz’s comparison of her mother to María Castro serves as a prime example of this idealization: “I thought Mom looked like her, the way she was driving, her back off the seat, leaning forward” (92). By likening her mother to a glamorous radio personality, Luz elevates her to a status of perfection and strength, which contrasts with the emotional instability that defined their family life. This idealized image is a coping mechanism for Luz, as she tries to hold onto a version of her mother that is untainted by the trauma and hardship they endured. In doing so, she creates a narrative that masks the pain, much like La Muerte offers a way to view death as something dignified rather than something chaotic and painful.

Luz further romanticizes her mother through the memory of the white straw hat, imagining her in a peaceful garden. In this fantasy, Luz envisions her mother’s back straight, looking poised and elegant, as if untouched by the burdens of life: “Mom turning around, her back straight, looking like María Castro” (93). The hat, an object her mother never wore, becomes a symbol of missed opportunities and unfulfilled potential, much like the emotional connection between Luz and her mother that was never fully realized. This imagined memory, however, contrasts sharply with the reality of her family’s breakdown and showdown, further emphasizing how Luz’s idealization of the past is a way to avoid confronting the true extent of their trauma. By focusing on this idealized image of her mother, Luz is able to distance herself from the painful memories that define her present reality. The unworn hat and the sun-drenched garden serve as symbols of what could have been—a life untouched by the randomness of fate and the trauma that shattered their family. However, this idealization only deepens the sense of loss, as Luz’s fantasies highlight the emotional distance between her memories and the realities of her family’s suffering.

Throughout Lotería, the randomness of the cards reflects Luz’s perception of her own life as shaped by forces beyond her control. The cards she draws dictate which memories she reflects upon, symbolizing the lack of agency she feels over her past and her future. In the same way that one cannot control the outcome of a game of chance, Luz cannot control the circumstances that have shaped her life—her family’s trauma, her mother’s absence, or her fractured identity. Yet, while the cards seem to strip her of agency, they also provide her with a framework for understanding her experiences.

In Lotería, Zambrano transforms the Mexican card game into a powerful metaphor for the unpredictability of fate, trauma, and identity in Luz’s life. The cards form a symbol of not only cultural forces but also personal ones, which creates her individuality. The randomness of these events influences her journey as well. However, it is through the act of telling her story that Luz asserts her agency, showing that while fate may be random, the meaning we create from our experiences is not. In the end, Lotería challenges us to see healing not as a linear process but as one shaped by how we choose to interpret the cards we’re dealt— reminding us that we have the power to give our stories purpose, even in uncertainty.

Work Cited

“Understanding the Impact of Trauma - Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services - NCBI Bookshelf.” NCBI, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/. Accessed 16 October 2024.

Zambrano, Mario A. Loteria: A Novel. Harper Collins, 2013.