Ashley Fermin ’27

Stitched From The Womb

No matter how a woman presents herself to society, people have found a way to create a conversation that centers on women as objects of sexual desire. As a young woman navigating the spaces I enter, I value artists who open dialogue on communal perceptions of women, and seek the answer to who we are as women beyond our reproductive worth. Artists like Georgia O’Keefe challenged the sexual narrative surrounding her paintings, insisting they were up-close illustrations of flowers and nothing more (Mannen 2020). Several feminist artists perceived O’Keefe’s works as examples of female eroticism, despite not being O’Keefe’s intent (Devine 2016). Over the last decade, the overt sexualization of women has become more common in media and entertainment, with every major entertainment industry adopting the slogan “Sex Sells”. A woman’s sex has become the only thing governing bodies internationally seem to focus on. In a time where the ability to reproduce seems to be all I am worth, art pieces that differ from this new norm, giving women more power and value than society deems they should, resonate with me the most.

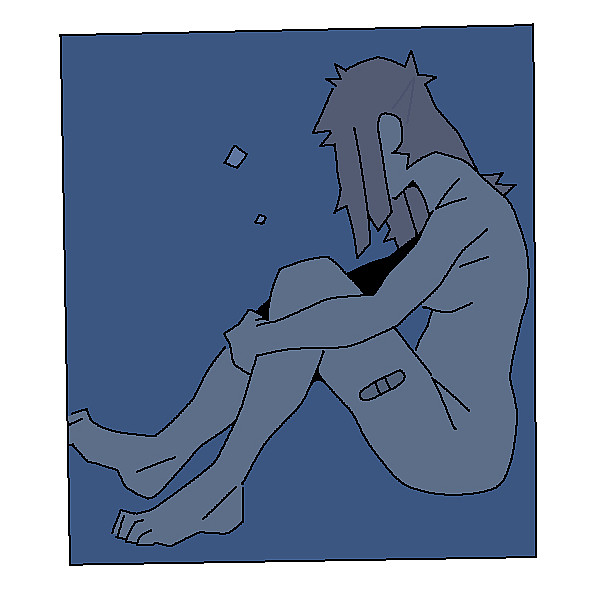

Seeing how women were viewed and regarded in other parts of the world inspired Judy Chicago to create the Birth Project in the 1980s. Chicago utilized the masterful needlework of hundreds of women to highlight the one experience that every woman on this planet is expected to take part in – childbirth. She created textiles like Smocked Figure (1984), Guided By The Goddess (1985), and Birth Tear/Tear (1985). These works do not uphold a fantastical image of what it means to be a woman; they defy the Western idea of creation and have the personal narratives of real women threaded within them. With this project, Chicago switches the narrative surrounding childbirth and motherhood, and shines a light on how few depictions there are of birth. In Smocked Figure , Chicago uses colorful embroidery to mark the silhouette of a pregnant woman dressed in a smock. The woman’s hands are covering her face, as if she were crying. Smocks are typically meant to be loose, comfortable undergarments. In this textile, however, the smocked figure seems constricted and unable to move freely. Mary Ewanoski, the embroiderer behind the Smocked Figure , linked the story of her mother who cried when she found out she was pregnant. Ewanoski admits that she felt like she was “binding the figure” with cross-stitches (Through The Flower 2016), as the Western world often does to pregnant women by placing the importance of the offspring above the human that is bringing that life to term. With this opus, Chicago sheds light on the unspoken truths about pregnancy, representing the realities of many women who rarely get to share their experiences and the internal conflicts that accompany creating a life. It is especially significant now, when women’s stories are so often silenced.

Birth Tear/Tear is a piece that shows the pain that comes with birth. The title has the homograph “tear”, as if to say that something is being torn and simultaneously that tears are being wept. The lithograph immediately grabs your attention: it uses different shades of red to portray a person giving birth while her children cling to her. The children are in the shape of a muscle, representing muscles being torn, something that can happen during childbirth. The second tear can be seen coming from the woman’s eye. She is crying, showing the pain that can come with childbirth. With this textile, Chicago renders an image of the violence that can come with motherhood and bearing children. It is not all gumdrops and rainbows – Chicago makes me feel empathy for the women who have to go through this, offering a perspective appreciated by the ones who experienced these tears firsthand.

Guided By The Goddess is a composition that aims to make a mother into a deity, returning all the power the world refuses to grant them. There is a figure in the top left corner pouring herself onto her children, endlessly giving as they reach for her. Chicago pulled from conversations with mothers who avowed that they felt similar to goddesses while taking care of their newborns (Through The Flower 2016). The screen print shows a necessary side of motherhood – to put the needs of another being above your own, what it takes to nurture and support, and the spiritual experience of that in itself. Chicago touches on the divinity and sacredness of motherhood, a common theme through the Birth Project.

Chicago delineates mothers as omniscient and puissant. She consistently portrays mothers as holy beings who are able to conquer and cope with all of life’s tribulations. What led Chicago to illustrate women in this way? Why did she feel it was necessary to weave the stories of women into these pieces, and how does the Birth Projectcomment on who people become when they enter motherhood?

Chicago first landed on the idea for Birth Projectafter developing an interest in the history of creation myths, specifically the myth of Genesis: the idea that man created everything and not the other way around (Bennetts 1985). This sparked her interest in art that would represent women as the foundation of all living things – a world that circles back to the matriarchal beginnings of society. Chicago uses the Birth Project to draw attention to the intricacies of motherhood with pieces that show fearful, powerful, and divine mothers of all kinds. Finding images of birth was troublesome, so Chicago instead spoke to numerous women who had experienced childbirth firsthand, and wove their stories into pieces like Birth Tear/Tearand Smocked Figure. She felt a need to share the unknown stories of these women, stating “As I listened, studied, and read I realized that it was not only birth I was learning about but also the very nature of this subject which was shrouded in myth, mystery, and stereotype. I knew that I wanted to dispel at least some of this secrecy” ( ThroughTheFlower). There is an unknown and untold side that Chicago aimed to unveil, and it makes these topics not only less taboo to the masses, but also removes the shame that women feel when speaking out on their experiences.

The material used to make these pieces was intentional and an integral part of this project. By using traditional women’s art of needlework and stitching, Chicago further honors women’s experiences and trifles with the Birth Project . Chicago states “We were using needlework to openly express and honor our own experience through this unique form which has both contained and conveyed women’s deepest thoughts and feelings throughout the history of the human race” (Chicago, Doubleday 1985). Using this medium, every piece in the project empowers women by utilizing needlework and the craftsmanship of female textilists in such a collaborative way that has never been seen before. Chicago felt “the textile arts had been undervalued in the art world and wished to elevate that art form (Dintino 2022).” Through this medium, Chicago uses the stereotypical “womanly job” of embroidery to further women’s empowerment with this composition.

Despite never being compiled in one place together, the Birth Projectis a piece that shows many of the struggles that accompany the maternal body, exhibiting the many faces of motherhood in the patriarchal society we live in. It is a timeless project, more relevant today than ever as women’s bodies are regarded as a commodity and something to take ownership of. With the overturning of Roe V. Wade being a topic of great debate, and every media outlet reducing women to their body parts, Chicago’s pieces shed light on the part of a child-bearing person’s life that is seldom discussed. Seeing the way Judy Chicago portrays the action of birthing and motherhood from beginning to end, gives room for a sense of solace, and access to positive representations that demonstrate and celebrate every part of it – parts that no government can touch.

Works Cited

Bennetts, Leslie. “Judy Chicago: Women’s Lives And Art.” Nytimes , 1996, www.nytimes.com/1985/04/08/style/judy-chicago-women-s-lives-and-art.html.

Devine, Kate. “Georgia O’Keeffe: Not a Woman Artist.” The State Of The Arts , 5 Oct. 2016, www.thestateofthearts.co.uk/features/georgia-okeeffe-not-woman-artist/.

Dintino, Theresa C. “JUDY CHICAGO’S THE BIRTH PROJECT (1980-1985): THE POWER OF PARTURITION AND TEXTILE ARTS.” Nasty Women Writers , 2022, www.nastywomenwriters.com/judy-chicagos-the-birth-project-1980-1985-the-power-of-parturition-and-textile-arts/.

Judy Chicago’s The Birth Project , Through The Flower, Belen, New Mexico, 2016.

Mannen, Amanda. “Georgia O’Keeffe Hated People Thinking Her Flower Paintings Are ‘Vaginas.’” Cracked.Com , Cracked.com, 21 Nov. 2020, www.cracked.com/article_29021_georgia-okeeffe-hated-people-thinking-her-flower-paintings-are-vaginas.html.