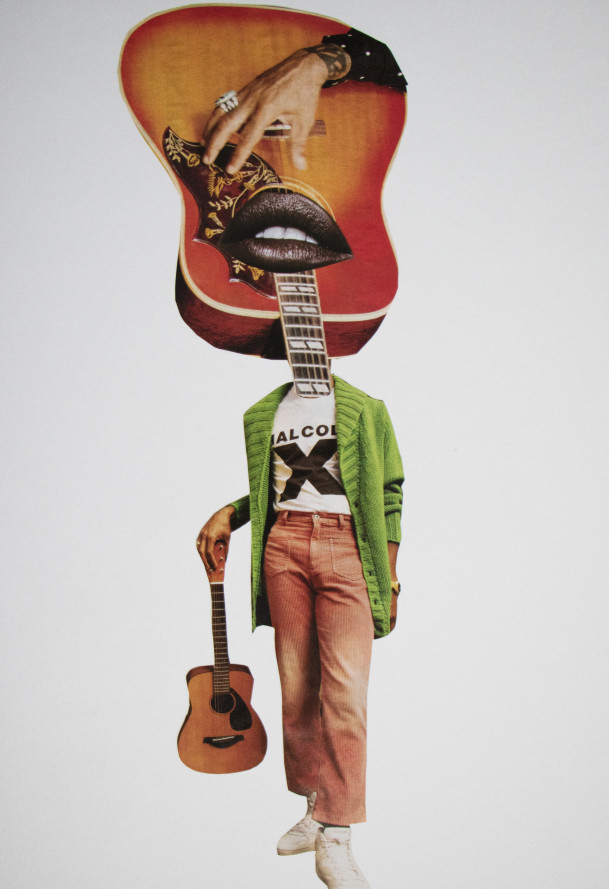

Thomas Carty ’22

What Makes an Album a Classic?

Introduction to Digital Publishing is an elective course for Communications and Journalism majors and an additional expository writing offering. During the spring 2022 semester, students wrote two studies, each imagined as destined for specific target publications. For the first, they had a choice between a personal essay and a “think piece,” one that expresses a strong personal opinion or idea. The second was a reported story. Senior Thomas Carty sought to determine what defines a classic album in a unique approach to the first project that integrates research and reporting. His final draft captures many characteristics of writing for the digital age—accessible language, short paragraphs, direct sentences, and profound ideas that are expressed in a concise fashion and leave the reader thinking for a long time.

The word ‘classic’ has definitely lost some of its heft over time, but making a “classic” work of art still seems important to many artists. Who wouldn’t want their album, novel, or screenplay to be considered a classic?

The problem is that the word “classic” is hard to define, particularly when it comes to music. Ask five people on the street what the characteristics of a classic album or song are, and you’re likely to get five different answers. Some may say “classic” means “really good” or “the best within its genre,” others may argue that classic means “most sales” or “most awards,” or work that has stood the test of time.

I’m curious if there’s a true metric to determine what makes a record a “classic.” I’ve looked at three records considered by many to be “classics”– Revolver by The Beatles, Thriller by Michael Jackson, and Blonde by Frank Ocean. These three records made enormous impressions upon the general public. What commonalities tie them together?

To start, none of these albums were the artists’ debut record. They’d already had some time to hone their craft, sound, and style. A few bands have released “classics” on their first go, like Pearl Jam, but most don’t hit their best work until they’re a few records in.

Secondly, each of these albums reached #1 on the Billboard charts. I don’t think chart position should matter, but there’s no better indicator of the public response.

Each of these albums has gone platinum, with Thriller actually going at least seventy times platinum, with over seventy million sales recorded to this day.

So it seems like chart placement and sales are important commonalities. What about the length of the album? It doesn’t seem to matter– Revolver clocks in at thirty-five minutes, Thriller at forty-two, and Blonde at exactly an hour.

Strangely enough, the success of the album’s singles are irrelevant as well. While Thriller yielded an incredible two number one Billboard hits, Blonde and Revolver had one single each, both failing to crack the Billboard top ten. It doesn’t seem like the singles are a decisive factor.

So how does a classic come to be, aside from sales? Artistically, what makes a particular album a classic? I’ve boiled it down to two components.

First, I’d say that a true classic can only come from an artist with a lot of work already behind them, and comes when they embrace a sound that could only come from them.

Revolver, Thriller, and Blonde represent new sonic ground for each of the respective artists. The Beatles had put out notable records before Revolver, but since it was their first album as a strictly studio-based group, they experimented with their sound like never before.

Thriller was the apex of Michael Jackson’s collaborations with Quincy Jones. Building on the dance hits from Off the Wall, they went in the direction of full, big-budget pop, and ended up creating the best-selling album of all time.

With Blonde, Frank Ocean experimented with soul, R&B, psychedelic rock, hip-hop, and ambient music, trading in the heavily-produced R&B pop of his debut record for an incredibly intimate, stripped-down experience.

But I’d wager the second and most important element in building a classic is the timing. Each of these records captured the zeitgeist immediately upon release. The Beatles spoke to the turbulent sixties when Revolver was released in 1966. The eighties introduced MTV and music videos to the industry, and the video for the title song “Thriller” became as culturally impactful as some major works of cinema.

Blonde was released in August 2016, at the height of an unnaturally bitter election season with tensions flaring across the country. The stripped-down, raw songs on the record reflected vulnerability and thus spoke to many at the time; today, they still offer a soothing release.

The importance of timing leads me to ponder, what will the next classic record look like? What will it speak to? The general mood of the country is sour at the moment. It feels like the zeitgeisty moments of the past few years are rooted in tragedy or violence. Look at the way Will Smith’s outburst at the Oscars dominated the national psyche. When is the last time a work of art did that? In this media-driven, hyper-stratified culture we live in, it’s harder than ever to create a work of art that touches everyone all at once.

In fact, I’d wager there hasn’t been a “classic” record or work of art since before the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, a few works of art captured the zeitgeist, such as the film Oscar-winning film Parasite and Lana del Rey’s album Norman F*cking Rockwell, which is Pitchfork’s highest-rated album by a female artist of the entire twenty-first century. Both of these works spoke to broader culture in unique ways. Parasite critiqued class and society. Norman F*cking Rockwell criticized idyllic American society, combining surf, folk, and rock music to paint pictures of a decaying populace craving escape.

But to quote Radiohead, “future’s bleak, so last week.” Sometimes, people want some distance from the current moment. For instance, La La Land performed well after the inauguration of Donald Trump likely because there was a demand for escape, and it was met by a colorful, big-budget movie musical.

While some great art has been made during the pandemic, I fear we may have lost our ability to collectively unite around it. Things have changed. The nation and world feels polarized to its ends. Social media has allowed consumers to retreat into their own niches, and it’s harder than ever for us to have a shared experience through art.

I have hope though. Art continues to be made. It’s just that a classic, a true classic, only comes around once in a while. It has to come from an artist at the top of their game in entirely new territory. There are so many young artists on the cusp of greatness. Due to the pandemic, many major artists have postponed and delayed their releases, allowing lots of new acts to take to the spotlight, such as Phoebe Bridgers, Arlo Parks, Jon Batiste, and more. I believe we’re in for a decade of great music and art. Sooner or later, another classic will speak to the complex moment we’re in. It’s too important for there not to be. Classic records don’t just improve the careers of the artists who made them– often enough they reinvigorate genres and inspire younger generations of artists. Most R&B singers have at least as few songs in the vein of Frank Ocean’s Blonde. Revolver has inspired almost every rock star under the sun. Without Thriller, Beyonce wouldn’t have been able to change the game with her albums and imaginative companion visual design.

I imagine that soon someone will come along with a new classic, opening a door to this new decade and embracing our increasingly uncertain future through their music. Classic works offer a glimpse of our current moment through the lens of music, after artists have had some time to fine their voices—they are the lifeblood of what makes art irreplaceable.