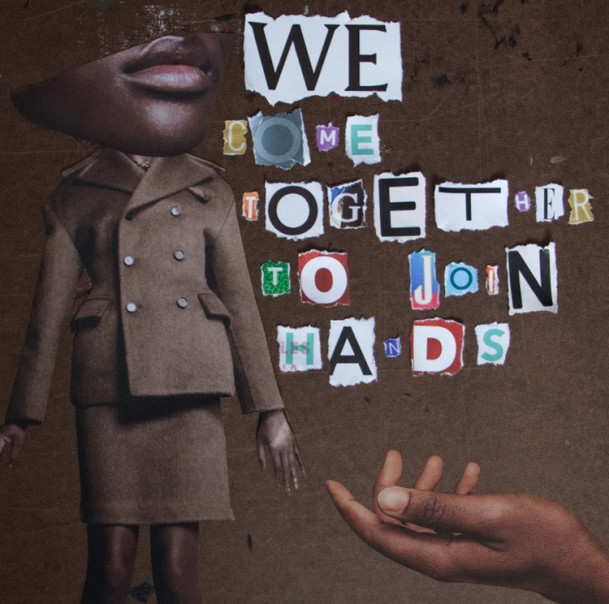

Ruby Holt Larsen and Abigail Luis

Passage Selection: “Mrs. Sen’s” by Jhumpa Lahiri

“This assignment is what I call a ‘passage selection.’ Students pick any length excerpt from the assigned reading and react in a page or two. They transcribe their chosen excerpt at the top of the page, and then they get into their reaction. Some students pick a sentence or two, and some choose a longer excerpt; it’s up to them. They are encouraged to engage deeply with the excerpt, and to try to tie it to any themes that they notice in the text. These assignments take place before we’ve had any discussion of the reading in class, so the students are reacting honestly and personally, and without the benefit of any explication from me or impressions from their classmates.”

—Professor Emily Sausen

In “Mrs. Sen’s,” an immigrant from India becomes the caretaker of a young American boy, Eliot. In their analyses, Ruby Holt Larsen and Abigail Luis explore the reality that multiple things can exist and be true at once. Larsen makes the point that Mrs. Sen is frustrated with her family’s expectations, while Luis remarks on her desire to return to them. These conflicting concepts etch the human need to better understand others in order to better understand themselves, and go well beyond fictional stories into human desires and contradictions.

—Barbara Kay, Expose Editorial Fellow

*

In Larsen’s selected scene, Mrs. Sen is distraught. Her family in India is invested in her new American life, without understanding that Sen does not live a life of grandeur, but the life of many middle-class people. Larsen describes “Mrs. Sen’s” as, “not a story for readers to curl up with by warm fire… Instead, it is thought-provoking and introspective, leveling the reader’s comfort in casual patriotism against the feeling of being an outsider in a new country.” The American Dream many immigrants imagine, is far from a dream. The adjustment to a new country and reality is much more difficult than Mrs. Sen’s family believes it to be. Larsen’s analysis of the “disparity” between fantasy and reality alludes to a deeper desire to return to familiarity. —Barbara Kay, Expose Editorial Fellow

“A Close Reading of Mrs. Sen’s”

By Ruby Holt Larsen

“Before he could answer, she took him by the hand and led him to the bedroom, whose door was normally kept shut. Apart from the bed, which lacked a headboard, the only other things in the room were a side table with a telephone on it, an ironing board, and a bureau. She flung open the drawers of the bureau and the door of the closet, filled with saris of every imaginable texture and shade, brocaded with gold and silver threads. Some were transparent, tissue thin, others as thick as drapes, with tassels knotted along the edges. In the closet they were on hangers; in the drawers they were folded flat, or wound tightly like thick scrolls. She sifted through the drawers, letting saris spill over the edges. “When have I ever worn this one? And this? And this?” She tossed the saris one by one from the drawers, then pried several from their hangers. They landed like a pile of tangled sheets on the bed. The room was filled with an intense smell of mothballs. “‘Send pictures,’ they write. ‘Send pictures of your new life.’ What picture can I send?” She sat, exhausted, on the edge of the bed, where there was now barely room for her. “They think I live the life of a queen, Eliot.” She looked around the blank walls of the room. “They think I press buttons and the house is clean. They think I live in a palace.” (Lahiri 125)

Jhumpa Lahiri’s “Mrs. Sen’s” is not a story for readers to curl up with by a warm fire; nor is it a heroic epic suitable for bedtime stories leading to miraculous dreams. It is thought-provoking and introspective, leveling the readers’ comfort in casual patriotism against the feeling of being an outsider in a new country. It tells the story of Mrs. Sen, and in the process, shows her commitment to her home culture and the struggle to assimilate into American day-to-day life.

In the above passage, more pointedly, Mrs. Sen is at a breaking point. She is practicing for her driver’s license–something she has been doing for many weeks at this point – and has received more letters from her family back home in India (113). Her family’s expectations about life in America are vastly different from her experiences. Where they assume that she’s living in the lap of luxury, she is cooking at home and watching another woman’s child to support the family income (111). The disparity between her family’s expectations and reality are enough to affect her, to the point of showing Eliot the first, more pessimistic glimpse into life as an immigrant.

The passage as a whole evokes a feeling of desperation, not just for Mrs. Sen to express herself in a language she is unfamiliar with, but for her to be understood and empathized with. She tears around the bedroom erratically, throwing carefully treated clothing around, and asks a series of rhetorical, hysterical questions (125). The distinctive smell of clothing in disuse as a sensory detail allows the reader to understand that though the questions she asks are rhetorical, she truly has many items in her closet that she hasn’t worn, since moving to the United States (125). Directly following this sensory detail, the readers learn more in terms of Mrs. Sen’s perspective. Her family’s expectations and beliefs on “natural” and “normal” American life create dissonance in the mind of the reader—while the reader knows that, comparatively, Mrs. Sen lives a comfortable life, her current situation is nowhere close to her extended family’s warped expectations. As a result, the reader is places themself in not just Mrs. Sen and Eliot’s shoes, but in those of her family. The reader is urged to acknowledge that their view of countries that they are not native to or travelers of is potentially flawed, subject or fallen prey to some kind of distortion. Whether or not this distortion is a romanticization, like that of Mrs. Sen’s family, depends on the reader. Regardless of the circumstance, the reader engages with a new perspective, and perhaps a clearer view of the world around them.

Works Cited

Lahiri, Jhumpa. “Mrs. Sen’s.” Interpreter of Maladies, Houghton Mifflin, 1999, pp. 111-135.

*

Abigail Luis evaluates the nostalgia of Mrs. Sen’s life in India and her odes to home in her everyday life. She notes that Mrs. Sen feels out of place, and feels just as foreign as the country she is in. While Larsen noted Sen’s frustration with her family for their obliviousness, Luis comments on her longing to still be with them, and how this hurts her than anything else. Luis reveals that Mrs. Sen is dueling with the past and present, and her expectations and experiences as she tries to adjust to her new life. Her husband, Mr. Sen, is a college professor who has already settled into a routine that suits the American standard. Mrs. Sen tries to explain this to Eliot as she hopes for someone to empathize with her in a country that is blind to the realities of other people, and where patriotism and privilege are woven together.—Barbara Kay, Expose Editorial Fellow

“Mrs. Sen’s”

By Abigail Luis

”Whenever there is a wedding in the family,” she told Eliot one day, “or a large celebration of any kind, my mother sends out word in the evening for all the neighborhood women to bring blades just like this one, and then they sit in an enormous circle on the roof of our building, laughing and gossiping and slicing fifty kilos of vegetables through the night.” Her profile hovered protectively over her work, a confetti of cucumber, eggplant, and onion skins heaped around her. “It is impossible to fall asleep those nights, listening to their chatter.” She paused to look at a pine tree framed by the living room window “Here, in this place where Mr. Sen has brought me, I cannot sometimes sleep in so much silence.” (Lahiri 115)

This selected text is from the short story “Mrs. Sen’s” by Jhumpa Lahiri, in which the young wife of a college professor takes care of and watches over Eliot, an eleven year old boy with a career-driven mother. The story follows the progression of their relationship over a few months as Mrs. Sen begins to unveil more of her past and her feelings as an immigrant from India.

This selection of text in the passage is the reader’s first realization that Mrs. Sen is struggling with her life in America. Earlier, there is a slight nod to Mrs. Sen’s appreciation of the life that she left. She wears traditional Indian makeup, such as a bindi. She also wears lavish saris, perceived by Eliot to be “more suitable for an evening affair than for that quiet, faintly drizzling August after-noon” ( 112). However, this remembrance of the knife is the first example of just how much Mrs. Sen is living in the past.

Mrs. Sen admires and loves her family very much, which is evident in the symbolism of the blade she uses to cut vegetables and prepare other foods. “My mother sends out word in the evening for all the neighborhood women to bring blades just like this one, and then they sit in an enormous circle on the roof of our building, laughing and gossiping and slicing fifty kilos of vegetables through the night” (115). By continuing to use this knife and prepare her food on the floor in the same way that her family would in India, she is honoring her heritage. Detailing how the knife would be used in a communal setting hints at Mrs. Sen’s isolation, as she now must use it alone. She is missing out on the social and cultural experience that she would have had with the other women in India, while in America she prepares meals alone as her husband is at work. Throughout the story, she continues to use this blade and treat it with great respect and care each time. This also illustrates her admiration of her culture within the story, as despite living in America with no other family, she still chooses to continue practicing her cultural customs alone.

While an appreciation of one’s culture is uplifting, Mrs. Sen feels so isolated within the memories of her past that she does not prosper in her life in America. She holds onto the past to the extent that it causes her pain. Instead of looking at the past as a learning experience to appreciate, she lives in it. Mrs. Sen goes as so far as to note the mental toll that living in America is having on her as she explains,”Here, in this place where Mr. Sen has brought me, I cannot sometimes sleep in so much silence” (115). Further, she relies on her past in order to function, which causes her to be unable to live in the present and look forward to the future that she finds herself in in America. Noisiness often isn’t preferable to rest, but this is the opposite for Mrs. Sen; Mrs. Sen relies on the togetherness in her community, and feels most comforted by the presence of others. Having an extroverted demeanor, Mrs. Sen has a difficult time allowing herself to rest without the presence of that familiarity. America is too different for her at this point in time to feel fully comfortable, as rest requires one to release their guard. Mrs. Sen does not feel completely at home in America, as she finds greater joy with her family in India.

This specific section of the text also draws significant attention to the isolation that Mrs. Sen is facing. She explains how Mr. Sen has brought her here, how he is the only other person that she knows in this country. Mr. Sen has assimilated to American culture easier than Mrs. Sen, as he leaves the house each day, drives, and works at the local university. Mrs. Sen is left alone in their apartment each day, isolated in a silent environment. This radical change from her bustling life in India full of community is highlighted in that section of the text, as well as the stress and depression it puts her under. Mrs. Sen fondly notes at any large-scale interaction she had in her community in India, “‘Whenever there is a wedding in the family,’ she told Eliot one day, ‘or a large celebration of any kind, my mother sends out word in the evening for all the neighborhood women to bring blades’” (115). It is said that Mrs. Sen always had some sort of community to look forward to. As she does not specifically detail what kinds of celebrations the women would come together for, it could be interpreted as Mrs. Sen not caring as much about the importance of the celebration, and more so the togetherness of community. She longs to be a part of such an environment again, however, finds herself in isolation. In America, Mrs. Sen is left only with her husband and the cultural practices she chooses to perform alone.

Work Cited

Lahiri, Jhumpa. “Mrs. Sen’s.” Interpreter of Maladies, Houghton Mifflin, 1999, pp. 111 - 135.