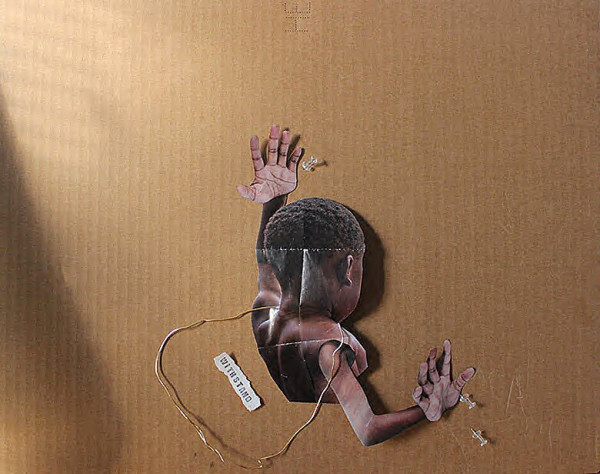

Leah Moser ’25

Springfield General Grabbag

I have been told that the first time I flew was at six months old, and rightfully so; some of my earliest memories are of airplanes. Airplanes and airports – the transportation of it all. Departures, arrivals, delays, cancellations. The sleepy-eyed check-in workers, the awkward pleather chairs, the instant coffee and the sticky carpets. I cannot say that I attach any pleasant feelings of nostalgia to these memories in particular, I don’t think I would be capable. This is not because of anything objectively bad happening; perhaps my childlike confusion as to why I kept being subjected to this experience may have simply calcified my aversion to it. Even now, I tend to avoid air travel at all costs. Being grounded gives me a sense of wellbeing that is unattainable within a claustrophobic airplane cabin. I am not saying that I wouldn’t indulge in a vacation to the French Riviera if the opportunity was presented, but the memory is enough of a deterrent for now. Hours upon hours of boredom, the stale smell of filtered air, the droning hum of cruising altitude, the total, inescapable immersion.

The actual reason as to why I was subjected to this is simple: my parents didn’t live together. They still don’t. They had met in Beijing about three years before I was born, while my Father was writing his PhD thesis on Chinese linguistics. My Mom, being from rural China and suffering from lack of opportunity, took advantage of her marriage to an American and obtained a green card shortly after my birth. My father, by this time, had fallen in love with China and refused to leave under any circumstances; so, my Mom and I moved in with his parents. This was a temporary arrangement, only for the few years my mom needed to earn her master’s degree. This is where the planes began – dozens of round-trip tickets to China and back just to see my father. Every summer, every winter, most Christmases. Even occasionally at random, like the one snowy February when my grandfather died. This is when, for me, The Simpsons began.

I will preface this next part by saying that I fully recognize how inappropriate it was for such a young child to be watching The Simpsons; I won’t deny that, but It’s not entirely my fault either. My father’s choice to live alone in China gave him the freedom to maintain the hermitic bachelor’s lifestyle that he preferred, but left him woefully underprepared for the few months a year I was in his care. The summer before my eighth birthday I was sent to Beijing for three months. This was the most time I had spent there since my birth, and the first time in my memory that I became acutely aware that I no longer spoke the language, finding even basic communication extraordinarily difficult. Childcare options also were limited, so my father signed me up for a cheap day-camp run by a local elementary school. I believe it must have been painfully boring. The only memory I’ve retained from those three months is playing tennis with a wall. No teachers, no students, they were irrelevant. Just the beating sun, the roaring cicadas, and a tennis racquet. Smack, whoosh, smack, whooosh. It’s really no surprise that I ended up restless; I had nothing substantial to keep me occupied. By July, I was bouncing off the walls.

Like most Americans, my grandparents would sit and watch TV for hours. It was their pastime of choice and one that they devoted significant resources to, at one point having at least six TV sets in their four-bedroom home. This tradition they passed on to their children, who passed it on to theirs. Television is an effective babysitter. My father knew this. At some point he finally let go of the reigns and gave me free access to his collection of bootleg DVD box sets. These were adult shows I wasn’t familiar with: Friends, 30 Rock, Seinfeld, Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and The Simpsons. Being a child, I gravitated to the show that looked most like what I had seen before – the simplistically animated cartoon with the punchy colors. I didn’t get it. The jokes didn’t land, the references were meaningless; but still, I remember laughing at the physical humor, so reminiscent of old Hanna-Barbera cartoons.The sense of comfort in this setting was so familiar, so quintessentially American, that it became the replacement for background noise. I didn’t understand adults anyway, but at least this was in English.

My first experience with The Simpsons may have been totally insignificant if I had never moved back to China, but I did. The very next winter in fact. It took me several years to accept this change as permanent, partially because I was being neglected by my parents. Being eight, I was old enough to have some independence, but not old enough to be able to fend for myself as I was expected to. I remember this period as confusing and painfully lonely. Language barriers continued to be a problem when trying to make friends or keep entertained, and the few resources provided to me were simply inadequate. In the bleakness of it all, I turned to The Simpsons, and devoured it.

It was no longer just a representation of America, it was America – and so it became my way of life. I’d get home from school and watch The Simpsons until bedtime, rifling through the boxes to find an episode I hadn’t seen yet. Before I knew it I had watched them all. 50, 60, 100 times over. It was a child escapists’ dream; a crude world filled with ridiculous, pointless characters that experienced no consequences. The format was basic: an episodic, non-linear sitcom centered around a nuclear family. I had seen it a thousand times before, but this show was different, it was edgy. I had become so disillusioned with the happy endings, the love, the wholesome embrace of a family that had been sold to me in America. The Simpsons, in their chaotic dysfunctionality, made me feel seen in a way I hadn’t before. They swore, they hit and choked each other; the Father was an alcoholic; the Mother was neurotic and repressed, and the children openly acknowledged their trauma. In a season four episode, Bart and Lisa sit on the couch casually discussing what new name they would adopt once they grew up:

BART: What are you gonna change your name to when you grow up?

LISA: (smiling) Lois Sandborne.

BART: (smiling) Steve Bennett.

The Simpson family lived in my version of the real world, one that wasn’t fair and didn’t make sense. It wasn’t trying to guide you towards some squeaky clean, oversimplified moral conclusion. In fact, it actively parodied the idea that one could realistically do so within the parameters of a twenty-minute storyline. A late season two episode ends with the Simpson family sitting on the couch trying to determine with (some difficulty) what the moral of their experience has been.

LISA: Perhaps there is no moral to this story.

HOMER: Exactly! It’s just a bunch of stuff that happened!

MARGE: But it certainly was a memorable few days.

HOMER: Amen to that!

Truthfully, there was something appealing about the idea that things didn’t always have to be that deep. As I grew older, the show grew with me. It was my predictable and static companion; offering the perfect solution every time I started taking the frustrating parts of life too seriously: laugh about it. The “bucolic splendor” of my childhood did indeed turn out to be a Kamp Krusty, but I wasn’t about to make a big deal out of it. Despite being incompetent in every way, Homer Simpson enjoys a wonderful quality of life, why couldn’t I?

My friend George recently contacted me after spending seven months in a Chinese jail over drug trafficking charges. I wasn’t necessarily surprised; we had started smoking weed together as teenagers and the habit has persisted, but it was still upsetting. This hypothetical situation we dreaded in high school was nothing compared to the horror of the real thing. My guilt felt endless; I pictured myself in his place.

One night when we were seventeen, we were smoking a joint in my living room when my father came home early. My hair stood up on the back of my neck, I thought for sure he would be furious, but he maintained a poker face for long enough to walk over and whisper to me, “Leah, I think you have a problem… this Simpsons addiction is getting way out of hand!”

I had forgotten that I’d put on a Simpsons DVD for background noise, but that was the end of it. He left us there and went to his room, amused and nothing more. George was impressed with the reaction, “I wish my parents would do it like that” he said. Who would have thought that the one with stricter parents would end up going to jail? I’ve been taught not to rely too much on stereotypes like that, though. Life isn’t a sitcom, consequences exist, and he went to jail instead of me. I can’t assign any meaning beyond that, and that’s ok for now. In the wise words of Homer Simpson, “Who would have thought a nuclear reactor would be so complicated?”