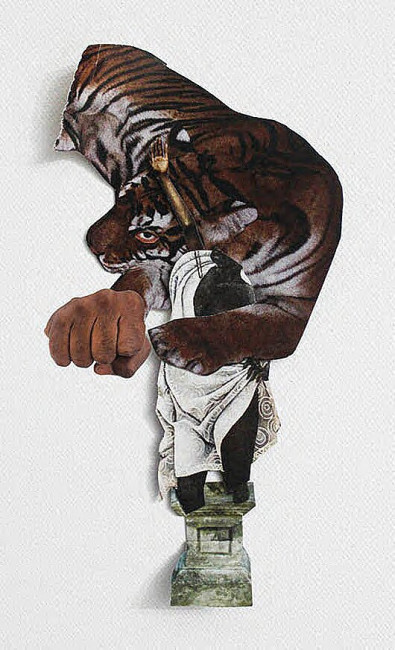

James Simiele ’25

Knockout

Within the circles of modern-day Christian Youth Groups, there is a ritual performed every week within the church’s gym. The game is called knockout, and in it, a group of participants line up with two basketballs. The person in the front of the line attempts to get their ball in the hoop. If they succeed, they circle to the back of the line and continue in the game. If they fail, they chase after the wayward ball and attempt to shoot again, while the person behind them takes the second basketball and attempts to get it in before their predecessor. Should they succeed, the person who came before them is “knocked out” of the game. This was the favorite pastime of the youth group I attended, every week, from age thirteen to sixteen.

I was never good at the game and would usually end up watching from the bleachers after getting eliminated in the first minutes of each round. That never stopped me from trying again. I was constantly jumping back in with the start of every round, hoping I would get better. I would sit on the bleachers alone and wait for the round to end to jump right back in. I was convinced that at some point I would find my place, not just in the game but in the group as well. I would just keep trying; if I was myself, then I would find the people who liked me for me!

That did not happen, and the self-loathing of thinking something was wrong with me began to creep in. After all, if I did my best to be myself and no one liked me, that meant I was not likable. I remember that exact thought process running in a loop in my head, over and over again. I would sit in the back of the teen room, hoping someone would sit next to me, only for the youth pastor’s wife to pity me as the only kid sitting alone and take the seat beside me.

Knockout.

The only reason I kept coming back was because of the small acts of service certain people would do to make me feel welcome. The basketball boys would let me in on a round of whatever game they were playing, or the popular girls would let me in on the latest gossip. The boys would decide I was just good enough to be cool for the day, and the girls thought I was interesting enough to keep around. I would think I’d finally found people who liked me being a part of the group. That is until the next week came around, and I was once again sitting next to the youth pastor’s wife.

Knockout.

I tried to make myself seen and heard. I would approach the pastor after what we called “Bible Time” and try to talk to him about the topics that had been discussed, only for the conversation to quickly disintegrate into small talk about the weather or whatever the results were of the latest basketball game he had coached. The same went for all of the kids that the youth pastor seemed to like more. No matter what obscure internet joke I referenced, conversation I tried to join in, or game I tried to understand, all of my leads led to dead ends.

Knockout.

After a while, anxiety joined the self-loathing. My sister would watch helplessly as I caved in on myself, usually sitting wherever I could watch life happen without having to participate. The anxiety of not understanding what I was doing wrong was crushing me, yet I kept coming back. I’d convinced myself that I had to keep trying because I had to make sure that someone would think I was worth talking to.

Over time, I began to acknowledge that I wasn’t what was wrong with that space. I saw kid after kid like me come in, test the waters for a few weeks, and then leave. I would watch conflict and drama happen, only for the youth pastor to step in and give a brief lecture to anyone involved, and then they’d all pray for the problem to go away. Rumors would start to fly about kids, and nothing would be done. One day, I watched as everyone decided to nickname me “James Charles,” after a trending gay YouTuber. Anyone who didn’t come up and directly ask me about my sexuality looked at me like I was contagious.

Knockout.

It’s a surreal experience, gaining the perspective you’ve been waiting for so long. That feeling of worthlessness began to go away once I understood that the people I’d been so desperate to gain validation from were not more important than me. During one of my final events with that youth group, I was given a Bible by the youth pastor. In the first few pages, he had written a short note about the things he had appreciated about me. That my “bright smile” and “contagious energy” would be missed, but he looked forward to seeing the man I would become. As he read the message in front of everyone, I knew that he had no real idea of the person I was.

I sat back down and listened as he closed the event, speaking about how proud he was of the seniors who were graduating that year. He said he was excited to see how God used us in the future, and he would love to catch up down the road. I haven’t seen or heard from him since I graduated high school.

Another knockout.

Knowing this place had done little for me over the past several years, why had I continued to go? I’d spent so long coming back because all of the authorities in my life told me that it was a good place to be. That it was the right place to be. I was yet to see it do much good for anyone except keep teenagers out of trouble by gathering them to play games a few times a month and telling them to stay away from the gates of hell.

Beyond that was the tunnel vision everyone seemed to be experiencing. There were overwhelming amounts of exclusion and isolation for so many kids because everyone had been taught these strict, diplomatic behaviors that detailed how to act, and no one stopped to consider how they should live. It affected every last impressionable young adult in that group, where anyone who couldn’t understand the personality they were supposed to put on was left on the outskirts to survive. Kids like me would come looking for something worth experiencing and would leave questioning if they even deserved it.

Knockout.