Luthier Sonberg ’25

A Father’s Son

I’ve always been told I have my father’s eyes, but our visions couldn’t be more different. And realizing that might’ve just saved my life.

On April 14, 2003, 12:30 pm, a young boy was brought into the world.

On April 14, 2003, 12:31 pm, a married man found out he was $20,000 in credit card debt, and promptly decided it was his wife’s fault.

On some random day in August, 2010. A young boy started Catholic school at Saint Peter and Paul’s, a grubby expensive place with vending machines of Vitaminwater and a ban on music. He wore ugly khakis and a shirt that was too big, a large smile on his face and not a thought in that head. He’d go on to cry during VeggieTales marathons and argue with the nuns over sonic lore and Beyblades. That kid was ridiculous and completely unashamed of it. He played Jesus’ body in a retelling of the crucifixion and would get in trouble for saying things he didn’t understand. He didn’t understand a lot. Hell, he didn’t even know what Star Wars was and still managed to play Jedi with the other boys. Although, he’d prefer to play the princess. “She has a blaster!”, he’d say “That makes her the strongest.” And he was right, who was going to tell him otherwise?

On some day in September, the same year a khaki-clad child got yelled at for wearing neon red cowboy boots to church, a ‘married’ man packed up his things into a bright white Ford pickup and set out for Texas. This was, of course, after telling his youngest son that they were practically twins. Two of the same soul just Xeroxed into different bodies and time periods. He put an ‘I heart Dad’ necklace on the rear view window and began the long drive from Tucson to Texas. There he did whatever ‘married’ men do in Texas. And whatever that was, eventually led to him losing that title.

For years these two lived parallel lives, completely unknown from the other. The young man would talk about how his father was a famous painter. “My father is named William! Sherwin-Williams is named after him!” But the boys father never said a word about that, letting his son pretend while he went to work painting rich people’s houses instead of portraits. But, even though they lived completely separate lives. Whenever they did intertwine, whether it be for the holidays or summer vacations, one phrase would be sung into the air like a sonnet by the bard himself.

“You’re just like me.”

“I want to be just like you!”

Nobody warns you when you’re a child about why caterpillars build cocoons. Of why that metamorphosis takes ages, or why it leaves that stupid bug in place and vulnerable for weeks. That’s something you learn through experience.

I learned about the caterpillar the summer I came to visit him in New York and my father refunded my plane ticket back home. The realization was both necessary and cruel.

I could either be like him,

Or I could risk disappointing him by letting myself be who I grew to be. Not just the bastard of a bastard of a bastard… of probably a bastard.

As you may be able to tell, I chose the latter. There was no titular moment where everything changed. No grandiose peak where the hero slaughtered the dragon and saved the kingdom and got hundreds of women to write him poems and sonnets. None of that. Just little breadcrumbs that lead to the world’s shittiest cake.

Maybe it started when I dropped Chinese classes. I was in a class for eighth graders when I was just in the sixth grade. They had been taking the class for three years and I was just brand new. All I remembered was Wǒ bù zhīdào, a couple of numbers, and the name my teacher gave me. But everything else was just a mess. My hands were too shaky to write the characters and information bounced out of my head with ease. I just didn’t understand any of the words that came out of Ms. Wong’s mouth. I went to my father, hoping he’d let me drop the class so I could at least pass the 6th grade. He did, thankfully. But not before Beaumont looked me dead in the face and deemed me “just like my brother.” This was a harsh insult in his eyes, because my brother wasn’t him. And that was a crime punishable by years of disgust and misdeeds.

“Your brother quit at everything he tried.”

My brother held a job and managed to help raise me while my father wasn’t there.

“He had no motivation. Your mother let him get away with everything.”

My brother quit baseball after suffering an arm injury during a game my father forced him to play.

“Don’t be like that. Be better.”

That was just fancy talk for ‘be like me.’

I closed my eyes, I bit my tongue, and set course to be like my father. Or at least the version of him that he claimed to be.

Maybe it was when I disappointed my father when I came back from Roger Williams University. I had just finished a three-week program about constitutional law on a full scholarship to the John Hopkins ‘gifted and talented’ program. And instead of summoning my internal Elle Woods I told him I wasn’t interested in continuing law. I found it boring. I found it cruel. I found myself dreading my daily 7:00 p.m. class argument session. And my father screamed, a horrible yell from the hollow of his stomach that echoed in our rat-infested apartment.

‘You’re wasting your gift. You’re so good at arguing.’

I wasn’t. I cried when he would raise his voice. I couldn’t stand the pain in my chest that came with defending myself from his wrath.

‘You’re just quitting again.’

How could I quit something I never wanted to do in the first place? I just was told I’d be good at it. And that was just because I was my fathers son. That’s all I was. I was just my fathers son. I didn’t belong to the world, just him.

That was of course until he formally declared me unworthy to continue playing his double.

The reason why changes every time I ask him. Sometimes it’s because he wanted to protect me. Sometimes it’s because he wanted to escape to Florida or even that I was ‘the butterfly effect ’ ; I still have no idea what he meant by that. But no matter how much the story changes one thing stays the same. I was no longer welcome home.

And as I stood outside 98 Hill Street, rain drenching my face more than my tears ever could, something dawned on me. If I couldn’t be my father, if I didn’t even want to be, what else was there? It may have taken months but I finally figured it out.

I wasn’t the lawyer my father demanded.

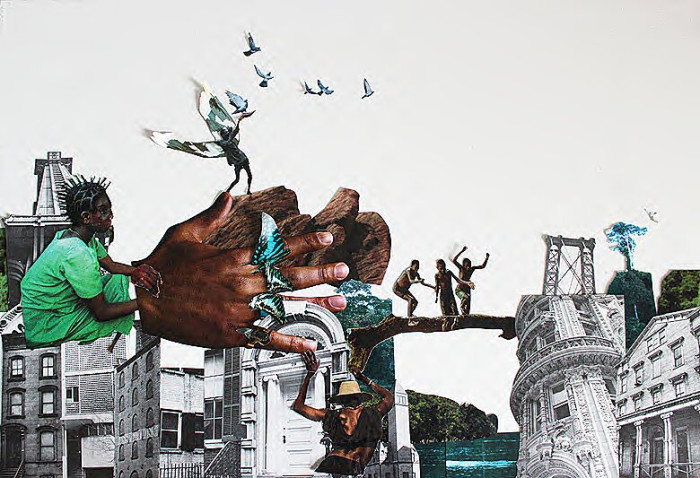

I was the artist he scorned.

I wasn’t the strong stone faced man with an axe to grind and void of tears. That was what he wanted. And I responded with tears in my eyes, unabashed and unashamed.

He wanted someone who could be the version of himself he never got to be. He had wanted to be a baseball star, a musician, a man with infinite money and women who had a perfect body and mind. A man who wasn’t defined by the title of a bastard, who tried to live up to the father he never got to meet. The version his mother would pay attention to. The version of himself that overdosed on ego and booze. The version he himself murdered.

And I no longer cared.

It wasn’t easy. It wasn’t easy to stop caring. To do that, I had to be someone I could care about. I had to reform myself without reference. At first, I still suffered from the symptoms of being William’s boy. I scoffed and insulted people for their interests, like he had trained me to do. And like a parvo-stricken lap dog, I hideously obeyed. And one day I finally looked at myself in the mirror. And wherever I saw him? I changed. I started with my hair, choosing blue over brunette. It was a simple action but it felt unbelievably freeing. From there I began to branch out and find things that I liked, started to learn how to enjoy without fear of scrutiny. My friends did wonders for that avenue, but I had to get myself there. I had to wake up each day and choose to be me. And now? That decision is one I make unconsciously and with ease.

I now wear slack jeans and nonprescription golden glasses that claim to protect my pale eyes from the screen. I laugh loudly and make fun of all the forms of ‘sports ball’ as I go back to my yellow dorm room to play bird themed dating simulators and listen to music sung by robots in pigtails and ties. I am ridiculous and unashamed.

And I now know why those caterpillars go into their cocoons.