Professor Ellen Brooks

Voice Lessons

“To release the imagination is to release the power of empathy.”

-Maxine Greene, educational philosopher

On a chilly afternoon in mid-November, our College Writing class meets at the Neuberger Museum of Art to tour the special exhibition of the work of Engels, a Haitian American artist who currently lives in Brooklyn. Engels, also known as Engels the Artist, blends painting, sculpture, and collage to capture the viewer’s attention. There is an unfinished quality to many of his pieces, and found objects are an integral part of the art—pieces of wood, staples, a washboard, a scrap of paper with words of love from a fan. To create, he follows his senses and draws on his childhood experience. Engels has said, “A work does not have to be one thing or another.” But knowing the artist’s intention does not change our instinct to imagine what his work means, and what he might be trying to say.

*

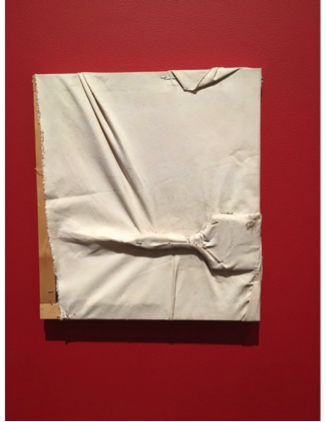

This is not our first visit to the Neuberger. Several weeks ago, small groups met and discussed single works by Engels. They talked about the details they noticed and then—their connections, inferences, and wonderings. Each writer composed a paragraph to describe, then analyze, and finally, to make a point about their viewing experience. Today, each group gives a guided tour of their selection, and the last stop on our tour is I Cannot Paint (2011). The group shares striking details: a brush trapped under the canvas, staples tracing the outline of the brush, the folds in the canvas, and the wood frame showing through the canvas on the left side—a characteristic element of Engels’ work. They consider the title, and the artists in the group joke that they can easily relate to that sentiment. They see humor and a playful spirit in the piece, and they wonder if the artist is making a statement about the insecurities that all artists face.

As we listen, we continue to study the canvas. When the group invites comments, Damon shares that he arrived a few minutes early, and while browsing through the museum shop, he discovered the catalog for the exhibit. The image on the cover is I Cannot Paint, and the title of the book, and the exhibition, is Art Got into Me.

“And now,” Damon says, “it all makes sense.”

Maybe, he wonders, the paintbrush is “under his {Engels} skin” or “like a second skin.” Later in the semester, Maeve will recall this moment as she writes a final reflection on her experience in this course: What Damon said about the skin and the brush inside it, I can look at things from a different angle and think about a scene or a work of art in a different way. I realize that while we are learning to look, we are also learning to listen.

*

In our classroom, we read for voice—short essays by George Orwell, Joan Didion, Neil Gaiman, Jo Ann Beard, and others. We read Anne Lamott’s “Shitty First Drafts,” and the writers in my classroom are smitten. Lamott’s advice to think of the first draft as the “child’s draft, where you pour it out and then let it romp all over the place,” sparks a conversation about taking risks and not worrying about what others think. The essay illustrates the impact that strong voice can have on the reader, and these writers express appreciation for Lamott’s message: “Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts.”

Tony Hoagland said that voice is the quality that compels the reader to follow the writer—it’s what grabs and holds our attention. In both settings—in our writing circle in the classroom and at the Neuberger, we notice examples of strong voice. It sparks our curiosity, fuels our wonderings, and awakens our imagination.

As a teacher, I grapple with how to teach voice. What can be taught, I wonder, and what can be learned?

Neil Gaiman writes, “This is not my face.” This line eventually becomes a mantra in our circle of writers. Gaiman tells us that when readers meet him in person, they often remark that he doesn’t look at all like what they expected. He declares that writers wear “their play faces to fool you. But the play faces come off when the writing begins.” As we read Gaiman, the idea of strong voice takes shape.

We write to capture our voice on the page. We move from personal narrative and memoir to writing about art. The recurring question we explore, as all writers do: How can we show the reader why our writing matters? We aim to reveal what’s at stake. If we are to achieve this, a strong voice is essential. Voice is a quality that is hard to define but when we hear it—when we see it on the page—we know it.

*

Capricia is a quiet presence in our class. At first, she politely declines my invitations to workshop her essay about the artist Arnie Barnes, but eventually she takes me up on the offer. An excerpt from an early draft reads:

Representation of black women in our society, culture, and media is hard to find, but when they are represented, they are seen as loud, angry, and ill-mannered….As a black woman, I’m tired of not being represented correctly. That’s why I love the work of Arnie Barnes. Barnes acknowledges the struggle black women go through and uplifts them. Arnie Barnes was a professional African American football player turned artist. Barnes’s paintings, “Study for Walk in Faith” (2000) and “Room Full A’ Sistahs” (1994), represents the African American woman as strong and resilient. He portrays black women as having endurance and uplifts them by highlighting their strengths.

One writer expresses appreciation for Capricia’s “honest” voice.

“I feel like I got to know you through this essay,” he says.

Another observes, “You made me want to contribute to the change that’s needed.”

Another comments, “I learned a lot about this artist.”

Kaiya says, “The voice on the page is loud and clear.” Others are quick to agree.

After workshopping Capricia’s draft, Kaiya wants to reveal her voice “like Capricia did—to let loose, get it out. To write free,” she says.

In an interview, Engels said, “While I’m working on any piece, me and the work become one. When you are in that place, you feel like your feet are not on the ground anymore. So this is what art brings me—it brings me a sense that I’m—I’m floating.

When a writer creates strong voice on the page, it is clear to everyone—including the writer. Later, during a conference, Kaiya comments that she is “really, really happy” with her final draft.

“Why?” I ask.

“My voice, I found it here. I think the way I really feel about these paintings and how they show police brutality is here.”

I notice that Capricia and her fellow writers are growing more comfortable with showing their “real” face, both on the page and in the classroom. Their writing creates a foundation for more than looking at art. As we look and talk about art together, we are beginning to see each other, beyond the surface details—to develop a habit of noticing that is a stark contrast to our everyday tendency to glean the world through quick glances, swiping and clicking and taking measure of one another in sound bites. In our writing community, we’re learning to look, and as we linger on the details—in our noticing the composition and elements that comprise a work of art, in our writing, in how we speak to one another about our work—we’re building a foundation for understanding. We are planting the seeds for empathy.

*

When I meet a student named Katie for a conference later in the semester, she places two handwritten drafts on my desk.

“I don’t think this meets the requirement of the researched essay,” she says. She explains that she feels that memoir allows her voice to emerge. I think of Hoagland’s description of strong voice: “When we hear a distinctive voice in a poem, our full attention is aroused and engaged, because we suspect that here, now, at last, we may learn how someone else does it—that is, how they live, breathe, think, feel, and talk.”

We talk, and Katie eventually decides to write “mostly” memoir, and to weave in the research and the art. Finding inspiration from Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, Katie begins the essay with a look back to her childhood:

Can you remember when it started? You search the recesses of your mind to pull out your earliest memory, but like so many of those clips and snippets of your life they are hazy with your innocence and the wearing away of the years.

As her essay takes shape, we learn about her life as an artist:

Years after leaving, you finally begin to process all of this through the art you create. Suddenly something that has haunted you for so long becomes inspiration. You decide to make a tea set shaped like female anatomy –you want to openly display the things you were taught to be ashamed of.

And then, a discovery in a studio art class further shapes the development of Katie’s point:

You lay your tea set out for critique and your professor tells you about a sculpture closely tied to this narrative of thought….Seeing The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago gave me the validation I needed to pursue the expression of my own thoughts…

Katie offers the reader a window into her personal experience—the “mostly memoir” narrative shows how this writer came to see The Dinner Party, and art, as a “force for change.”

Katie’s essay, like so many others in our writing community, affirms my long-held belief that the arts must play a central role in education. This practice of looking at art gives us common ground to share our differences, and we all end up learning from each other. We’re curious to hear what others notice, and we celebrate the divergent voices in the room—the voice that invites us to view the world from a new or different vantage point. When Katie imagines her way back to her childhood and links this to her artistic process, she invites the reader to imagine her narrator’s experience in the world. Katie’s encounter with The Dinner Party informs, inspires, and shapes her view of art as a way to re-shape her own narrative and perhaps to nudge us all towards creating a more caring and more inclusive world.

*

At the end of the semester, I ask writers to reflect on the course, hoping to find new insights to inform my teaching. I ask: What will you remember and what will you forget? Even in a list of words, phrases, and short sentences, their voices shine through. Common themes emerge when writers share what they’ll remember: voice, how to find my voice, looking at art, how a painting or a photograph can be a mirror or a window, workshopping our essays, and visits to the Neuberger.

I highlight this response: I learned how to observe.

And this one: As a writer, I’d use the process of letting myself “float” as Engels said. If I allow myself to float, I’ll allow my thoughts to take control of my writing rather than to second guess and doubt myself. I think of Katie and how certain choices allowed her to “float”as a writer—to feel the sensation of moving pen over paper, to think in story form, to dive into revision in search of voice and meaning.

I know that I may never get a definitive answer to my questions about how to best teach writers to discover their voice. Each semester is different, each writer enters the classroom with a particular vantage point and set of experiences—and there is no single writing process for all. And perhaps, I need to reframe the question. Instead of what can be taught, I might ask, “What does the writer need?”

Reminding myself that these writers are also my teachers is essential. For it is their writing and their reflections on the process that will illuminate the conditions that support the development of their voices. Writing about art offers a context for taking risks—starting with the details that the writer notices, and then shaping a narrative that reveals what matters to the writer. As one writer said, “I learned that I really have to make everything that I write important to me somehow.”

I aspire to create a community of writers where every voice will be heard. I take a step back, picturing moments of discovery during the semester—in the classroom, in the museum, or at the writer’s desk—examples of the strong voice that we notice in what writers say and in what they write. And I realize just how much their words got into me.

Works Cited

- “An Interview.” Art Got Into Me”: The Work of Engels the Artist, edited by Patrice Giasson, Neuberger Museum of Art, 2019, pp. 14-21.

- Engels. I Cannot Paint. 2011/2019, Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, New York.

- Gaiman, Neil. “These Are Not Our Faces.” The View from the Cheap Seats: Selected Nonfiction, William Morris, 2016, pp. 93-94.

- Greene Maxine. “Imagination and the Healing Arts.” The Maxine Greene Library, 2007, p.4, https://maxinegreene.org/uploads/library/imagination_ha.pdf, Accessed 16 January 2020.

- Greene, Maxine. Releasing the Imagination: Essays on Education, the Arts, and Social Change. Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1995, p. 19.

- Hoagland, Tony. The Art of Voice: Poetic Principles and Practice. W. W. Norton & Company, 2019.

- Lamott, Anne. “Shitty First Drafts.” Bird by Bird. Anchor, 1995, pp. 21-27.

- Rankine, Claudia. Citizen: An American Lyric. Graywolf Press, 2014.