Jean Ings ’23

The Families of the Lower West Side

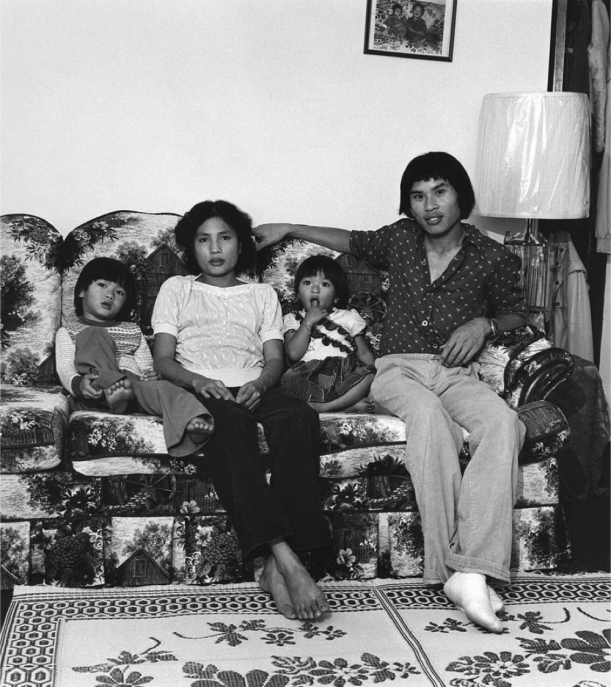

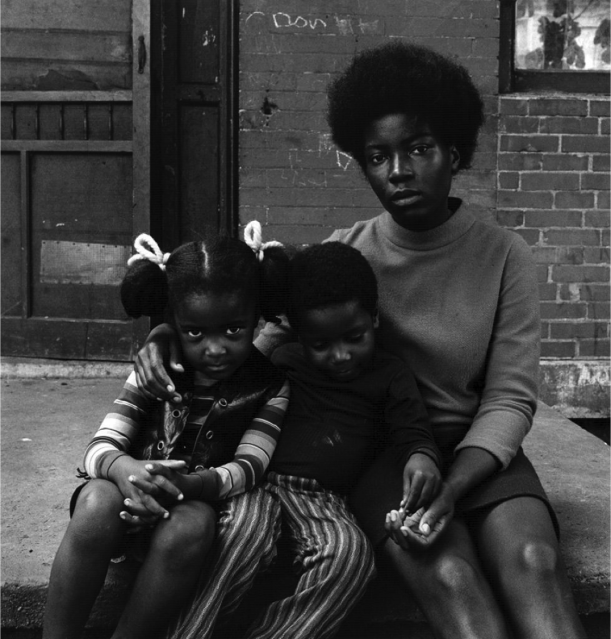

In his Lower West Side Series, Milton Rogovin showcases the many faces of Buffalo, New York. He chose this neighborhood because he wanted to present the ethnically diverse area that was close to his work, not only to better know his neighbors, but to display to the world what the Lower West Side means to him. This photo series is comprised of approximately 140 photos spanning from 1972-1977. Two family portraits, one of an Asian family sitting on a couch, and the other of a black woman sitting with her arm around a young boy and girl, similar portray families of people of color living in the Lower West Side of Buffalo in an intimate and comfortable light, challenging preconceived notions that those living in poverty are somehow dehumanized by their circumstances.

The Asian family consists of a father, mother, and their two young children, on a cotton upholstered couch. The father wears a dark top, light pants, and white socks, and sits with a laid-back posture, leaning slightly on the arm of the couch as he gazes at the camera. Next to where his right arm drapes over the back of the couch is a lamp, still covered in its plastic wrapping, on a side table. The mother, wearing a white top and dark pants, sits barefoot and slouched with her hands resting in her lap. She holds a tired expression while looking slightly beyond the frame. The two children sit next to their parents, the younger one sits cross-legged with his thumb in his mouth looking blankly out of frame, while the other sits with his right foot propped up on the couch, glancing curiously at the camera. Behind them is a photo hanging on the wall of the two children sitting on the same couch as they are on now, when they were younger.

This family portrait shows a charismatic father, seemingly eager to take a photo with his family, a mother, who appears tired, and the children, curious about the world around them. The photo that hangs behind the family allows the viewer to see the growth of the family over time. While only giving the viewer so much to look at, this photograph has a larger story to tell.

The second photograph shows a black woman and her two children sitting together on a concrete ledge outside their home. The mother sits with her right arm protectively around the two children, with the other arm resting in her lap. Wearing a turtleneck and pencil skirt, she stares directly at the camera. Next to her sits the young boy, who sports a black top and striped pants. He seems almost unaware of the camera, his attention focused on his mother’s hand as he intertwines his own hand into hers. With her mother’s hand resting on her shoulder, the girl gives a quick yet curious glance at the camera. She wears a striped top, skirt, and white bows in her hair, and sits with her hands folded on her knees. Behind them is a beat-up background consisting of graffitied bricks, as well as the front door of their home that has a broken window.

The daughter, who at first glance seems to be mimicking her mother’s gaze at the camera, actually chooses to look at it begrudgingly. Her mother’s arm keeps her close, the body language between the mother and daughter suggesting the girl’s restlessness, and how she may not want to have her photo taken. Her brother, on the other hand, proves to be more camera-shy, focusing on his mother rather than looking directly at the camera. This family portrait, unlike the first one, is taken outside the home in this family’s neighborhood. Here you can see the contrast in the family’s clothing and the condition of the surrounding area.

*

Rogovin displays these families in a way that counters some of the negative connotations that have been pinned on the people living in the Lower West Side area. Looking at these photos provokes a similar feeling as revisiting old family portraits. The fact that we get to see inside their lives, makes us feel at home and part of the family. After taking a closer look at both photographs, one wonders what is not shown. What was it like to live in the Lower West Side at that time, and how did that affect the families portrayed in the photographs? In addition, what about Rogovin—what were his views on the conditions of the Lower West Side?

Milton Rogovin grew up in Brooklyn, New York in a Jewish family. After completing his degree in optometry he moved to Buffalo to pursue his career. Rogovin began his work as a documentary photographer at the age of forty-eight after he refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, a choice that ruined his career as an optometrist. His voice silenced, Rogovin turned to photography. Through his photographs, he not only spoke up for himself, but for the people around him. Choosing to photograph the people of the Lower West Side, Rogovin wanted to focus on what he considered “the forgotten ones”: people who were left underrepresented and underappreciated.

*

The photographers of Humans of New York carry a similar vision for their work. Vinson Cunningham’s addresses the photography for HONY in The New York Times, “Photography has long been used instrumentally, if not to tell stories in this contemporary sense, certainly to call attention to various social realities.”

Rogovin decided to focus on the parts of Buffalo that are areas riddled with poverty, unemployment, drugs, and prostitution—but Rogovin saw beyond the cracks in the cement, focusing on the flowers that sprouted in between. Verlyn Klinkenborg writes of Rogovin in The New Yorker: “He found an openness in their faces, a directness, that says a great deal about his candor and empathy.”

Klinkenborg expresses admiration for Rogovin’s empathy and his ability to see beyond the surface of a human being to see the real stories hidden underneath. We see this through his photograph of the Asian family sitting on the couch, or the African-American woman and her children sitting on their doorstep, both conveying family and togetherness.

Although his initial career path was damaged due to forces outside his control, Rogovin was able to find a new medium to express himself and help others along the way. Rogovin chose to photograph people of the Lower West Side to tell their stories and encapsulate them in time so that they could never be forgotten. In some cases, Rogovin would photograph the same people over time, creating a triptych that would show the subject grow and change (Klinkenborg).

*

Buffalo is unofficially segregated, with people of color typically in the city, and more Caucasian residents in the suburbs. Reading about Rogovin and his background, as well as his heartfelt views on the people of the Lower West Side, gave me hope for a better Buffalo. Rogovin not only gave us a window into his subject’s lives, he allowed us to see past the judgment and preconceived notions that accompany such separations, giving us a clearer picture as to who they are. His photos are raw and truthful, embracing the challenges the residents of the Lower West Side experience, while also highlighting the people who undergo these misfortunes in a positive light. In an interview for his documentary, The Forgotten Ones, Rogovin expressed how the people he photographed cried when they saw their photos hanging in a gallery rather than a police department (Wang). Seeing past the negative aspects of this part of the Lower West Side, Rogovin truly believed that all people have great potential and wanted to show that in the most honest way possible: a photograph.

Rogovin wanted to showcase the people of the Lower West Side in a way that we can empathize with—a way that doesn’t cast his subjects as “other.” Rogovin creates a window into the lives of the families he photographed; there we rub our sleeves in circles on a foggy glass lens to find more to the story. We stare and analyze, trying to make sense of what we see beyond the glass— until we see our own reflection.

Works Cited

- Cunningham, Vinson. “Humans of New York and the Cavalier Consumption of Others.” The New Yorker. 3, Nov. 2015.

- Klinkenberg, Verlyn. “Milton Rogovin.” The New York Times. 5 Feb. 2011.

- Wang, Harvey. “The Forgotten Ones.” Youtube, uploaded by Travelinglight56, 14 Dec. 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HN5wm_Kxvi4