Jalyn Cox Cooper ’23

Bound to Free

When I tell people I hated high school, they usually believe that I’m exaggerating. It feels as though the anger, loneliness, and stress I felt during that time could be overlooked since I had no bills to pay, no “real” job, and no children at home to take care of. For some people, high school is an eye-opening stage of life, and it certainly was for me, too. Sometimes though, I can’t help but feel disappointed in the environment I was forced to learn in. High school was difficult, not simply because of academics, but because the community was socially and emotionally constricting. Since leaving that environment, I have been trying really hard to become more comfortable with myself. It is something I work on every day.

I went to high school in a suburban town called Brockport, just outside of Rochester, New York. Like many small towns, the people in Brockport were like-minded and shared the same identity: white, straight, cis-gender, and conservative. Students of color only made up about one-tenth of the student population. We were already viewed as outsiders, and many white students made sure all of us knew it, too. Swastikas appeared on the bathroom walls and under desks in classrooms. Many students of color were called the n-word, and other racial epithets, and Latino kids were referred to as “illegals.” Just about all of us heard the phrase, “Go back to where you came from,” at least once. There were barely any consequences for this behavior. Time after time, my friends and I would report these issues to our administrators, only for them to take as little action as possible. The same thing would happen over and over again.

During my freshman year, one of our principals created the Instagram hashtag #bhsinspires, intending to highlight positive things going on in our school. Of course, this was not what happened. Soon, the hashtag was being used by anonymous accounts with random names. These accounts posted things like pictures of Emmett Till’s mutilated body, Hitler and Nazi soldiers, KKK members, and many more unsettling images. There was even a picture of a white man morphing into a picture of a Klansman with the caption, “When the black girls are being loud at 7 in the morning #bhsinspires.” That particular post scared me more than the rest of them. I felt like a target.

My friends and I, all girls of color, would meet each other in the morning and just look at one another silently. There were no words to describe that kind of fear. I was scared to come to school for a long time, and I told my mom I wanted to transfer, but she wouldn’t let me. It became hard to focus in class because that hashtag was all I could think about. Any of my classmates could have been behind the creation of those accounts, and I would never know. Students cracked jokes about it that made my stomach churn. To them, the whole thing was funny. I resented them, while in silence. When I reported the issue to the administration, I was told that there was nothing that could be done, since the accounts were anonymous. I was angry and frustrated, but just tired of trying, so I dealt with the fear in silence.

This is only a small fraction of the kind of hatred I had to deal with during high school. Being ostracized due to one part of my identity made it hard to be open and proud of the other parts—the ones I kept to myself. I struggled with coming to terms with my sexuality for a long time, and in some ways, I still am. My classmates were no better to queer and trans students than they were to students of color. I didn’t want to be talked about even more than I already was, so I kept that part of me a secret.

*

My junior year of high school put me in a bad place physically, mentally, and emotionally. I had so much work, and instead of stepping up my work ethic, I procrastinated. Each night, I’d push off my homework until around nine or ten o’clock and finish very early the next morning. I slept in class constantly since I was so tired. I ate horrible food quite frequently and gained a lot of weight, which also had a negative impact on my self-esteem. I had a hard time finding things that excited me or made me happy about life, and it was really hard for me to share that with the people around me.

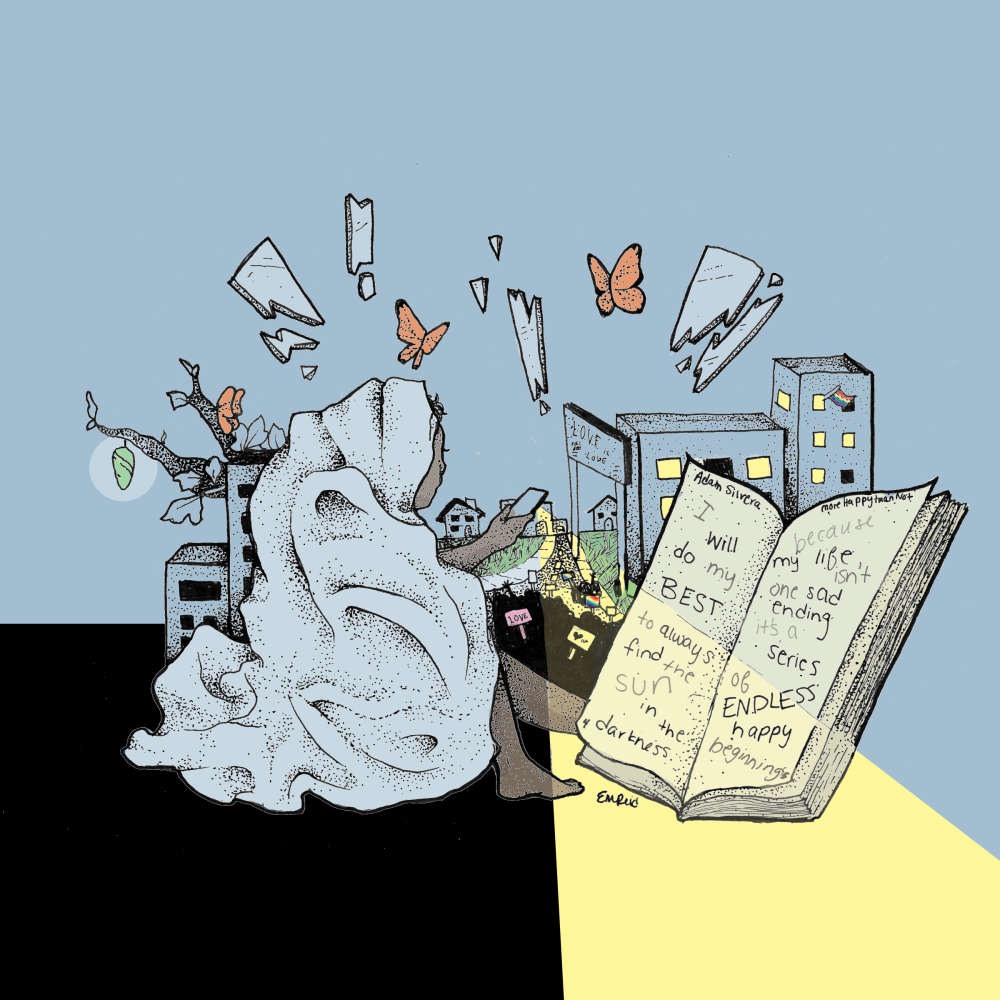

Sometime during that year, I bought a Young Adult novel called More Happy Than Not by Adam Silvera. I had read and loved another one of his books called They Both Die at the End, so I decided to read this one as well. Once I started reading, I couldn’t stop. More Happy Than Not follows sixteen-year-old Aaron Soto, a Latino boy living in the Bronx. After his father’s suicide, Aaron is trying his best to feel happy again and starts to do just that through his newly-developed friendship with a boy in the neighborhood, Thomas. As their friendship progresses, Aaron realizes that his feelings for Thomas are romantic, which causes his life to spiral out of control. It’s hard for him to grapple with the realization that he likes boys, especially due to the homophobia in his community. When Aaron tells Thomas that he’s gay, he feels scared, thinking, “This silence makes me uncomfortable, like I’ll never be comfortable again. If I play my cards wrong, I’ll not only lose my privacy, but maybe rob myself of my happiness too” (135). He then says to Thomas, “Obviously I’m scared for my throat being [gay] around here, but I’m not exactly rushing to tell everyone tomorrow” (135). This fear of coming out and being treated badly because of it is something I related to on a deep level. Reading this reminded me of my own school environment. The way I saw it, being open about my sexuality wasn’t worth the possibility of being ostracized, and for a long time, I sacrificed my own comfortability to avoid feeling like an outcast.

Over some time I was able to gain a little courage. The first people I told about my sexuality were my friends, the ones I had been attached to since the sixth grade. I told them one day while walking to class that I found this girl in the grade above us (who had just walked by) really cute, following that statement with, “By the way, I like girls, I guess.” I was so embarrassed to say it out loud that I couldn’t even look at them. They reacted like I thought they would: kindly, happily, glad that I felt comfortable enough to be so honest about it. Like Aaron, I only allowed the people I trusted the most to know who I was in that way.

Aaron’s inner conflict only grows stronger as the story progresses. He even considers getting a “memory-relief procedure” done by the Leteo Institute, which could help him forget that he’s gay in the first place, saying, “I don’t want to second guess if my friends are going to be okay with me being me… I don’t want to see what happens if they’re not… I’m doing myself a favor in the long run if I can somehow book a Leteo procedure” (157). Later on, Aaron’s friends overhear a conversation between him and Thomas where they talk about the time Aaron kissed him, even though Thomas doesn’t feel the same way. When Thomas leaves, Aaron’s friends all gang up on him. Even his best friend Brendan tells him, “It’s for your own good,” just before the group jumps him, punching and kicking, and eventually throwing him through a glass door leaving him incapacitated.

I remember reading this part of the book in the dark of my room with only the flashlight from my phone to help me see. I was crying so hard. It was too real for me. This reminded me of all the stories I’d heard in the news about queer and trans people getting assaulted and sometimes killed for kissing their partner in public or dressing a certain way. Aaron, though he is a fictional character, suffered a fate that is not unlike a lot of LGBTQ people in real life. Many of us are terrified to exist as we are because the world will not accept us. I felt this way about my school, and about certain members of my family. I knew the people who mattered most wouldn’t care, but the fear of knowing that someone at any moment would call me names or hurt me in any way was too scary for me to even care about what I’d gain from being my most authentic self. It wasn’t worth it.

I think my connection with Aaron speaks volumes about how much oppression dictates the quality of one’s life. Though Aaron was from an urban community, and I went to school in a suburban one, both of us lived in communities that were very constricting, where claiming our identities led to ridicule or attack.

“Happiness shouldn’t be this hard,” Aaron says in the book.

And he’s right, it shouldn’t. Treating people kindly should not be conditional, but universal. This is why it is so important to have spaces that are judgment-free, where everyone is accepted no matter what they look like, who they love, or what they can do. I often wish I went to a school that was more accepting, where I didn’t have to hide who I was or water down my very being. But I can’t change that. I am very much a product of my experiences, positive and negative, and they have made me stronger. Reading More Happy Than Not helped me realize that despite external factors that may impact certain aspects of my life, it is my job to define my own happiness and assure that I reach it.

One of the main reasons why I chose to attend Purchase College was because it felt like everyone was accepted there, no matter who they were, or how they identified. The strange part is that even now, at a place like this, I still don’t like talking about my sexuality, or who I may be attracted to at the moment. In writing, I have managed to, for the very first time, put all of my deeper, intrusive thoughts into words. I am still afraid and still uncomfortable— but I don’t want to be this way forever. My hope is that being in an accepting, loving environment will help me reach a point where I accept my whole self for who I am, and refuse to whittle away at parts of my identity for the sake of others.