A Peek Into the Collection: Irene Rice Pereira

For the next two NEU Student Voices blog posts, art history master’s student and Neuberger Museum Archival Research Fellow Rem Ribeiro joins me in examining objects in Roy R. Neuberger’s permanent collection.

Most but certainly not all of the artists whose work Mr. Neuberger collected were Caucasian males. For our project we chose works by two trailblazing female artists. We started by looking at pieces by Irene Rice Pereira, an abstract painter and philosopher who played a major role in developing Modernism in America.

Analyzing the Work

Rem Ribeiro

Irene Rice Pereira’s conceptual and formal elements within her expansive oeuvre can be best attributed to that of the Surrealist movement and the period just after. While taking a deep interest in psychoanalysis and philosophy—more specifically, cosmology, metaphysics, and existentialism—she also considers the Surrealist artist’s desire to embody and utilize various forms of media.

During her first solo exhibition, a critic is said to have thought so highly of her abstractions that he referred to the artist as “Mr. Pereira.” This assumption of a male artistic genius bled into the following dominant art movement in America, mid-century Abstract Expressionism. However, in opposition to the formal elements popularized through the movement, Pereira denounced the aesthetic approach of flattening the canvas picture plane. Rather, Pereira’s work allows for a deeper and personal connection between art and audience; her geometric shapes are contained within the canvas, coexisting in between one another across seemingly infinite planes in the fore-, middle-, and backgrounds. To add introspective depth and energy, Pereira is known for using textured bases, such as glass. What she does share with some of the Ab-Ex artists is the desire to thicken, carve into, and mottle the application of paint onto a surface.

Despite her incredible feats towards discovering the human psyche through her synthesis of actual light perception and optics existing outside of the picture plane, McCarthyism’s denouncement of intellectualism and gender dynamics played a major role in the growing gap between herself and the art world. It is through works such as Deep Vision (1949) that one can truly experience the dexterity Pereira holds when balancing spirituality and science. Much like her writings, Deep Vision proves that, in Pereira’s own words:

“Only a woman could have dealt with the irrational infinite and given it form — humanized it.”

Pereira’s Connection to Roy R. Neuberger

Gabrielle Bohrman

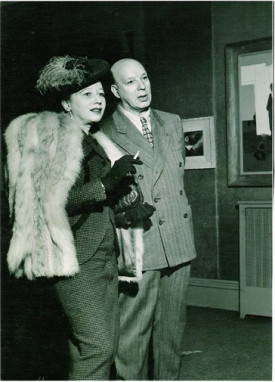

When Neuberger purchased Deep Vision in 1953 following a retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum, Pereira was enjoying public interest but remained largely excluded from the Abstract Expressionist canon exhibited today. Most scholars argue that this is due to her own self-alienation from the 20th century contemporary art scene, marked by an independent style that does not fit into any categorization. Irene Rice Pereira, The Wind Blowing the Seed – with Greetings, undated, From Roy R. Neuberger's 50th Birthday Book, 1953, Ink on paper, 9 1/8 x 8 inches, Collection Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York

Neuberger, who collected what he liked as opposed to what critics promoted, may have been drawn to her for this reason.

Pereira’s artistic techniques were greatly influenced by her role as a founder and teacher at the Design Laboratory, an industrial arts school established in 1935 and funded by the Works Progress Administration during the bleakest years of the Great Depression. Based on the Modernist Bauhaus movement, the school’s curriculum emphasized chemistry, physics, and the use of experimental arts materials. During this time, Pereira read Howard Hinton’s The Fourth Dimension and became fascinated with the space-time continuum. She later wrote her own theories regarding the relationship between art and cosmology, symbolism, and psychology.

At the time, artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning followed the Modernist trend towards medium specificity (i.e., creating works that were specific to the medium they used). In the case of a two-dimensional painting, they sought “flatness.”

Pereira rejected this trend by keeping her abstract forms within a controlled perimeter, that seem to emerge from the central area. Her unique techniques to create a three-dimensional effect distanced her from her contemporaries. This “order out of chaos” effect reflected her philosophical enlightenment.

Whitney Director and curator John I. H. Baur wrote that her approach was “… half mystical, half scientific, and wholly personal.”

Evident in Deep Vision, Pereira also created texture by scratching and cross-hatching paint strokes, activating light within her paintings. And, unlike her abstract predecessor Piet Mondrian who also worked with geometric forms in a primary palette, she used a variety of tones and hues. This could have been an attractive factor for Mr. Neuberger, who said he loved the skillful use of color.

One year after its purchase by Mr. Neuberger, The Whitney Museum included Deep Vision in one of their first exhibitions in their new location on West 54th Street in New York City; this was the first time a museum opened its doors with a major show of 100 art objects from Mr. Neuberger’s personal collection. The show was extremely popular and later toured museums and galleries in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Washington DC.

The second Pereira work in Mr. Neuberger’s collection, The Wind Blowing the Seed, is from a book containing personal notes, letters, cards, and drawings given to the collector for his 50th birthday in 1953. Compiled by Mrs. Neuberger, the book contained works from 37 artists in addition to Pereira, who considered Mr. Neuberger a friend. In his personal memoir “The Passionate Collector,” Mr. Neuberger says, “this is the book I treasure above all else.”

Gift of Roy R. Neuberger, 1997.13.01.25

The Neuberger Museum acquired Deep Vision in 1976, and The Wind Blowing the Seed in 1997; both are now contained in the permanent collection.

A look through the registrar files showed that Mr. Neuberger frequently borrowed objects including Deep Vision that he previously donated to the Neuberger Museum of Art to hang in his own apartment. This hints that the piece was likely one of his favorites since he enjoyed admiring it from the comfort of his home!

Deep Vision was also popular with gallerists and museums based on the number of requests for it to be exhibited.

Stay tuned for our next post as we explore the works of artist Faith Ringgold.

Gabrielle Bohrman

Neuberger Museum of Art

Fall 2020 Communications Intern

NEU Student Voices Blogger

Rebecca Elisabeta Marya (Rem) Ribeiro

Neuberger Museum of Art

Neuberger Archival Research Fellow, 2020-2021

MA Modern and Contemporary Art, Criticism, and Theory, M+ Curatorial Studies track